by Greg Ruth

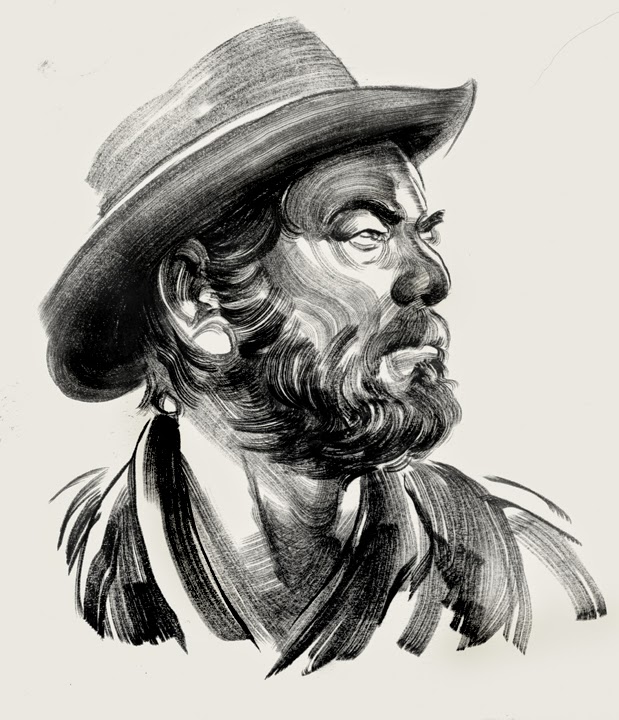

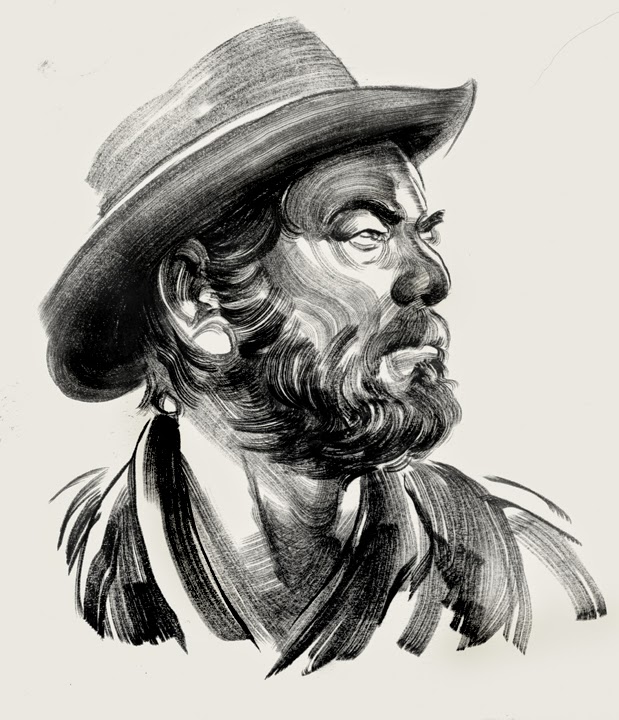

|

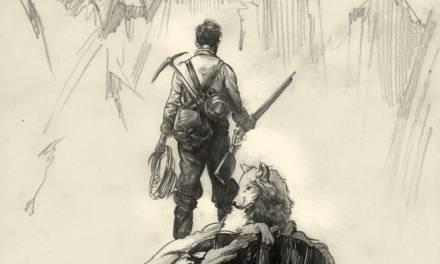

| The terrible Mr Ward, from INDEH |

This post says it’s about comics, but really this applies to all storytelling in general. While my views are entirely my own, no matter how much I bloviate as to their merits, they remain mine and mine only. For me the most important aspect of any storytelling is character. You get this wrong, the rest doesn’t matter… but get it right, well now you’ve really got something. We’re coming out of an addicton to high-concept narratives or twisty twists that have us spinning around so much in place we don’t notice how flat and utterly boring most characters in these stories are. Clever left turns or overly clever plot points or settings are like a candy bars: they taste great and are utterly satisfying while you’re chewing on it, but it’s over minutes later and you’re still hungry. Create a character people believe in and they’ll follow that character anywhere. Create a plot point and you’ll only take your audience as far as the plot point’s end. Even worse, the reader will have now reason to come back and read it again. We re-watch Star Trek episodes, reread Tolkein or the Dune books because revisiting those stories is like reuniting with an old friend. They are places we want to go to again. They are a kind of home that way. Clever hooks, plot points, single line story grabbers sell books and stories more easily, that is a fact. The mistake comes when one confuses the tag line with the story- remember the commercial is not the product it’s trying to sell. Make your story about something, no matter how goofy it is, and make the most effectively painted characters go through its trials and you will leave your publishers and your readers hungry for more. The best compliment you could ever get as a storyteller is to have someone ask if there’s going to be another one. Here’s a few simple pointers to help you get there:

Places are a character too.

Beyond the fabulously weird literal interpretations of this as in Grant Morrison’s brilliant Danny the Street, the transexual moveable city block from the Doom Patrol comics, you should treat your location and setting with the same diligence as you characters. As much as it matter to build up your character with qualities to make them desirable and worth caring about, you settings and places should be attended too in much the same manner. Why is this place here? What is the history of this house? Is there a little crack int he window where a bird struck it last week, still un-repaired? Is it still yellow because the owner just doesn’t have the wherewithal to paint a color he likes? The more you bestow your places with character, the more you add to the story’s overall strength of purpose. The more effective anything you do there becomes, especially as it ties to how we may read it from a place of our own choosing and meaning.

Cliches can be your friends, but mostly they’re the other thing.

Cliches derive from some originating truth, but the cliche has at this point overtaken whatever reality it stems from to render that argument meaningless. We like as an audience to see the next stage of the basic character cycle- the reverse cliche. The hooker with the heart of gold, the tough biker who maintains a Hummel collection, Spock crying. These are all obvious by virtue of citing the cliche they are reversing. It’s a reflection in a mirror and not as a fact, entirely different. My usual advice is to take a character and add at least a third wrinkle to them and see how immediately they become something more.

|

| Dancy Flamrion from ALABASTER |

Pretty does not equate with empathy.

One of my favorite examples of this mistake is the film, Cloverfield. Not a work of high art by any means of course, but who cares about that. the idea of a Godzilla film told via cell phone footage or whatever could be epic, and in some respects it achieves that. But it suffers almost entirely from the key problem of confusing handsome attractive characters, devoid of much else. In this particular story the problem is catastrophic because in order for the drama to be meaningful, you need empathize with them, not delight in seeing them all get crushed because they look like d-bags out of a Abercrombie and Fitch catalogue. If you’re goal is to do this, then push that all the way to its most intense extreme, but generally you should not. Imagine that film with the cast from say, The Wire. Imagine that you wanted to see them survive and how much more it would have been if they had bothered to achieve this basic hurdle. The knee jerk thing to do in telling a story with a character is to put forth the prettiest ideal- the fantasy version. But really it’s far FAR more effective to avoid the fashion runway and make them look like your Aunt Helen or Uncle Morty, because even beyond the novelty of that approach, tangible real characters are the epicenter of what makes most stories function. A thriller is more thrilling if you care about your character’s fate. A horror story more horrifying, and drama more dramatic, and comedy is more hilarious. It’s the difference between the silly yawn fest of Friday the Thirteenth as compared to the narrative genius that is The Babadook.

This isn’t to say ugly is the solution immediately of course, but if you’re finding this hard to bend to, go for ugly and see what it teaches you. And let’s face it when we’re talking about actual beauty we really mean something more than sexy vampires or the posters out of Tiger Beat. Find the flaws, the human characteristics and make them paramount.

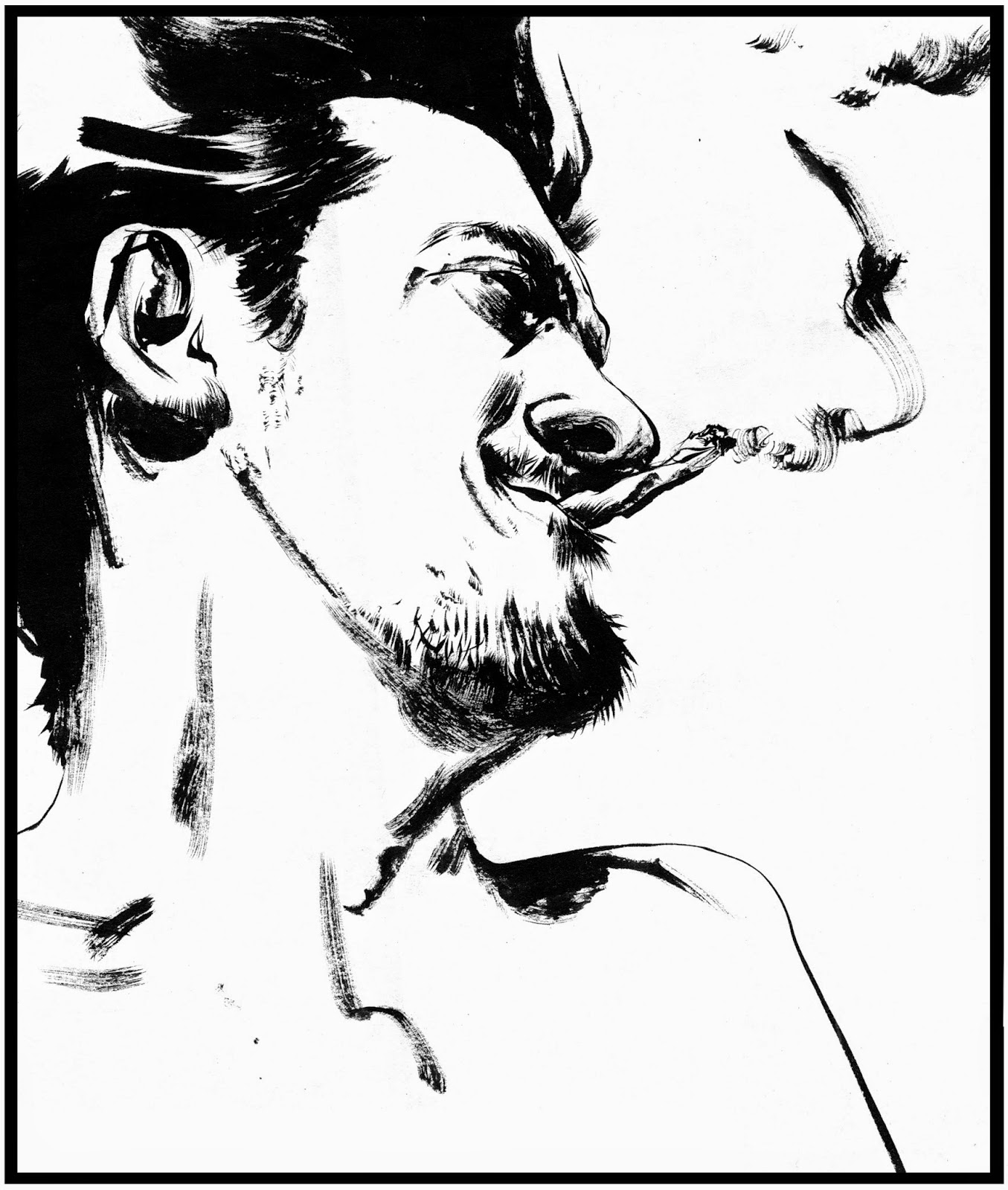

|

| Milo Tulpa from THE CALENDAR PRIEST |

Don’t take your characters too seriously.

Know the difference between being dramatic and being maudlin. Don’t tell me why the character is supposed to be sad, make them cry as if all you need to do is tell me they’re crying when you really should be crafting them in such a way that I am crying with them whether I want to or not. Pay serious attention to them, but don’t become so entangled by them that you lose an editorial perspective on what they story needs them to do. Remember: you’re making things and playing pretend up for money. It’s a ridiculous job to have by any measure, so lighten up and have fun. Don’t be afraid to counter sad moments with humor or the reverse. Keep a wide range of emotions in play as this will enable the character to be more real, and by association, more readable and fun to experience.

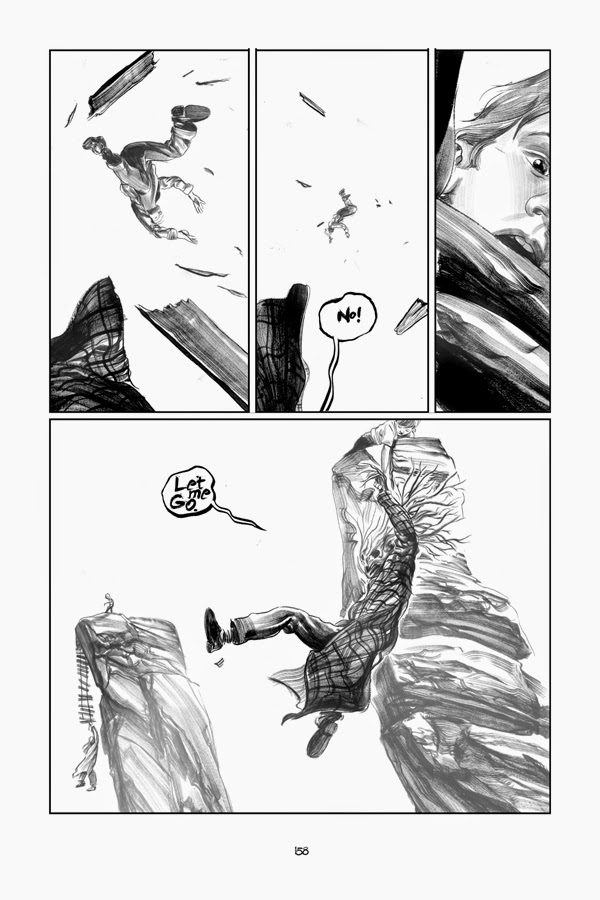

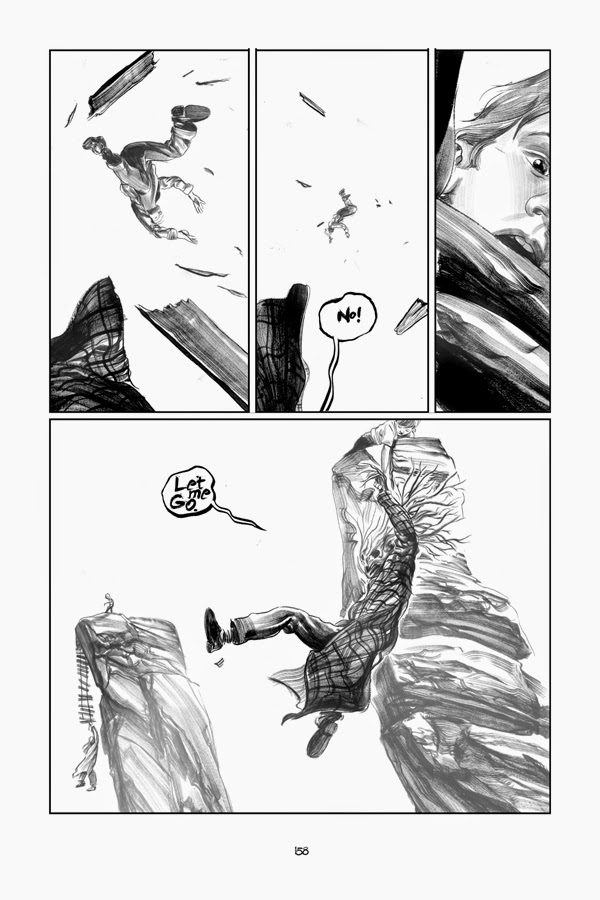

|

| Pamela Sweetwater gets got but not gone, from SUDDEN GRAVITY |

If you don’t believe in your characters, why would anyone else?

Seriously- you are your first and sometimes only fan. So be a true fanatic and love and be your characters. By a hat they would wear, and wear it while writing him/her. Find all the details of their lives that have brought them to this place even if you never once mention any of it in your story. It will inform your character’s most essential qualities and shape their responses in a way that will only make them richer on the page or screen. Think about their voices, what their breath smells like, keep crafting all the little bits that make a person in your head until that magical tipping point comes and they start talking back to you. If you’re doing this right, this will happen. You’re not crazy, you’ve only finally achieved a character that is rich enough to be on its own, and argue with you when you make it do things counter itself. This crazy is the sound of success.

Get outside your comfort zone.

If you make stories about bunnies and teddy bears, use that ethic to tell me a story about biker gangs on Mars. If your schtick is the woman’s point of view, use a man’s. This is not necessarily to say you should go all anti-Woody Allen and refuse to write what you know, but more as an exercise to see what you’re about by playing in a sandbox you’re not about at all. We find and define ourselves by what we are not. We only confuse ourselves by thinking we are what we imagine ourselves to be. So flex some unused muscles and get out of the yard for a bit. You’ll craft far richer and more varied characters this way, and despite the fear of doing it, you’ll have fun too.

|

| The Laamia Berry explodes, from THE LOST BOY |

It’s great to use magic to get a character into trouble,

disastrous to use magic to get them out.

This is an old Pixar-ism, and one of it’s most essential truths. The basic thrust being that leading a character into a trap by a fantastical device can be world building and powerful, whereas using some similar device to save them from defeat, is lazy and rends the character from its own agency. Indiana Jones is more exciting to see in action as compared to say, Moses because he survives his trouble by being able to exploit opportunities and accidents to his own ends. Moses has God’s ultimate lightening bolt to hide behind, and so there’s no real threat to him, and thus no agency or interest in that way. The most famous of this kind of mistake goes back to Bobby Ewing stepping out of the shower after being dead for a year and simply writing it off as that whole year being in fact, a dream. Or in the case of Interstellar, saving everyone by invoking broad concepts like “time”, “gravity” and “love” but refusing to buttress these ideas with any realities within the story. It’s fine to surprise your character with a last minute gift that saves him/her- be it a lifeline jungle vine that drops just before Indiana Jones before the boulder crushes him, reaching your hand behind you fro the Doctor’s as a monster comes at you from the front. Magic in this case is a previously unsupported trick of the narrative that hops in only to rescue the character from a plot-trap the writer won’t invest in a more clever way to escape from. It’s sanguinely bad writing at its core, but it’s worse than lazy because the pretense carries with it the scolding of one’s character fro refusing to play along with the saving grace. So have fun getting your characters into trouble, but make sure you allow them to enjoy getting out on their own. Anything else is dull at best.

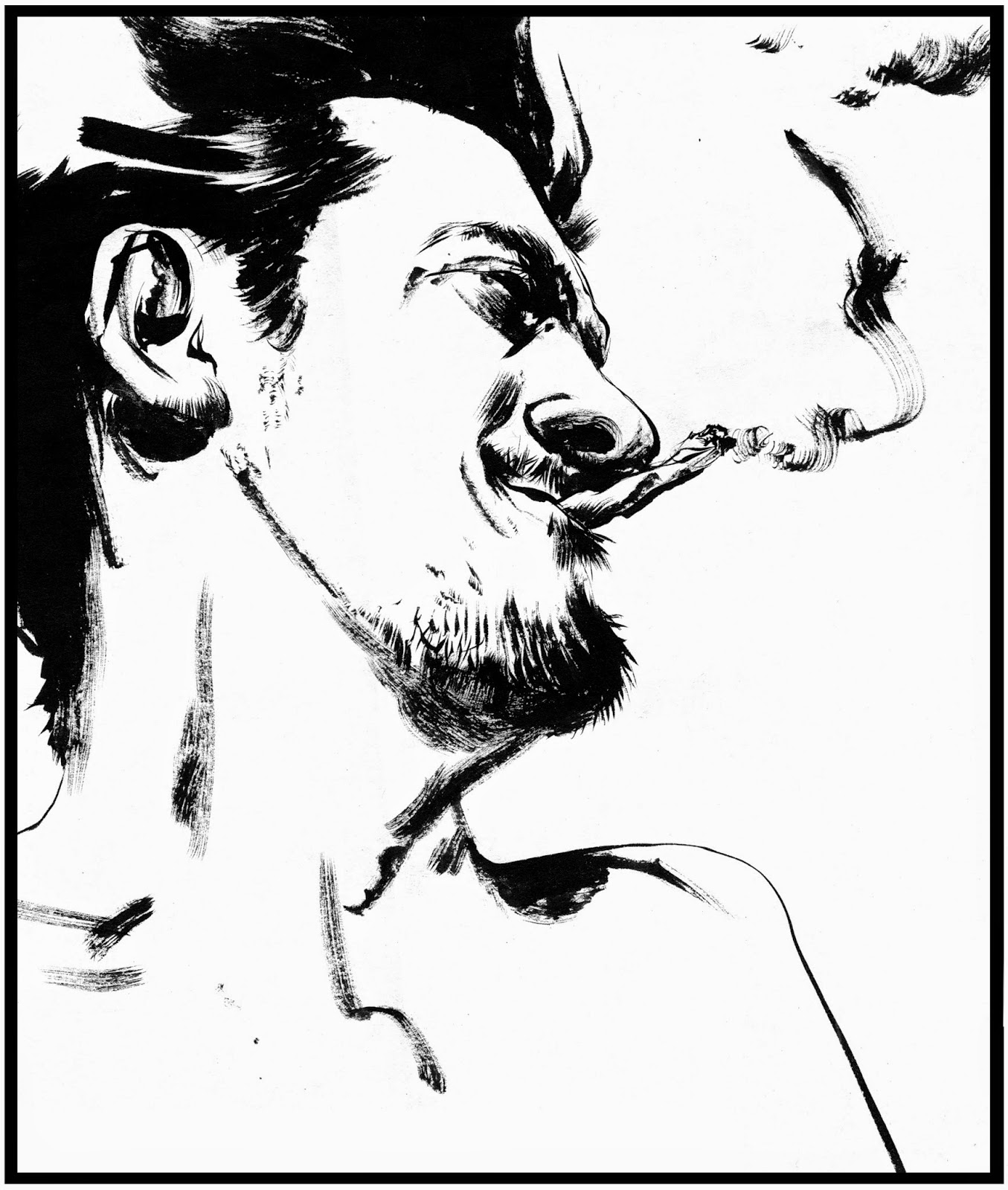

|

| First draft of the death of Haloran from THE LOST BOY |

Don’t be afraid to say goodbye.

This is mostly for the writers out there, and something both entirely difficult and more overwrought and poorly executed than most. Whether you’re killing Superman, Sherlock Holmes, or Wolverine, kill them dead and be merciless. Avoid graveside maudlinism, overwrought emotion in lieu of plot. You don’t need to be cruel but you have to make something like this count and you must have it make some kind of sense- or if it doesn’t and it’s just your guy getting run over by a train by accident, then make that cruel randomness the point. The hardest thing for a writer to do is to let go of a character, especially if that character has lived with them for so long. It’s also the easiest to screw up too because the writer’s emotional investments make it hard to see the difference between eulogizing a character’s exit and making that exit meaningful to others reading the story. Again, the more real world weight and quality you apply to your setting and characters, the more transparently goofy a melodramatic hacked out end will feel. Respect the work you’ve put into the character, the story and all the rest by really taking time to get out of your comfort zone and make it count. You only get one shot at this, so try and aim true.

These are so inspiring and fun to read! How many parts are you planning to write if I may ask?

Great read! Thanks for sharing.

I had intended a solid twelve articles in this series…. but, I guess I'll keep em coming until the fuel runs out. The more I get into the aspects of comics the bigger the possibilities of comics to get into. Like trying to measure the square footage of the inside of the Tardis. This may take some time.

There really are appreciated Greg. It's not easy to break things down into digestible chunks and still make them profound. The caveat of “this is how I do it” is an appropriate way of saying that guidelines have been built from experience so have a good reason for straying. Thanks again.

Great post, Greg. I like the quote from Chuck Jones: “Forget about the plot. Personality is the key. An idea has no worth without believable characters to implement it.”

That's it completely. One of the things I adore most about comics is while there are certainly ways to do it well, and functional rules you can follow… you can also totally forget most of them and go nuts. Any advice about the medium is just a personal experience. I won't always be relevant to others, but it's nice when it is to some- thanks.

Thanks James- I LOVE Chuck Jones. I think it's easier to come up with a catchy schtick or high-concept plot than it is to invent grow and develop a tangible interesting character that endures. We don't care what happens to Bugs Bunny, we care about what he DOES.