By now most of you should be more than aware of the new series of Sherlock Holmes stories from Stphen Moffat and Mark Gatiss and the BBC. If you’re not, you should be. It is one of the most successfully brilliant examples of an updated version of any old story- and Sherlock Holmes is OLD- that has come since Stephen Spielberg remade Moby Dick in the form of JAWS. One of the marquee achievements is in stark evidence via its pilot episode, “A Study in Pink” which puts Holmes and Watson together for the first time solving their first case of a series of coerced suicides, while also laying down the first breadcrumb to Sherlock’s ultimate foe, Moriarty. Moffat is a technical watchmaker of a narrative structures. His Rubick’s Cube style of story structure that solves itself just in time every time is not to be trifled with and regardless of all the various strong opinions about him or his work, one cannot discount the sheer intellect behind what he makes and writes. Much of the casting remains in place with minor changes here and there. All changes are improvements as are all reshot scenes. THe former seems like a typical low-fi BBC reboot of the infinitely rebootable Sherlock Holmes mysteries not really advancing much beyond the setting and modern adornments. The final version pushes the entire retelling into deeper and more groundbreaking territory. It simply does what it’s former twin accomplishes, but triples its import, effect and purpose.

I’ve gone through and posted here, as you can see, side by side comparisons of each of the identical moments where the same dialogue is being delivered to compare and contrast the vast differences.

What makes is relevant here for Muddy Colors, and anyone interested in storytelling, is that we have two completed versions of this exact episode, both the final aired version amd the unaired “pilot” version that preceded it. What makes this such a rare treasure is that both were shot from identical scripts, but each by different directors and with some essential different narrative approaches that make comparing them an incredibly essential case study for how to tell a good story and then how to do it better. And the aired pilot is certainly better by miles. Being able to witness the first draft and then the changes that make the final is an absolutely priceless lesson in how one attacks and makes better a story. Whether you write or draw or paint, you are making the same kinds of choices any narrative person would by rote. Blocking out how and where we see a thing, how we portray it, stylize it, present it and from what perspective are all aspects we must consider if we’re to make successful stories or art- and always both.

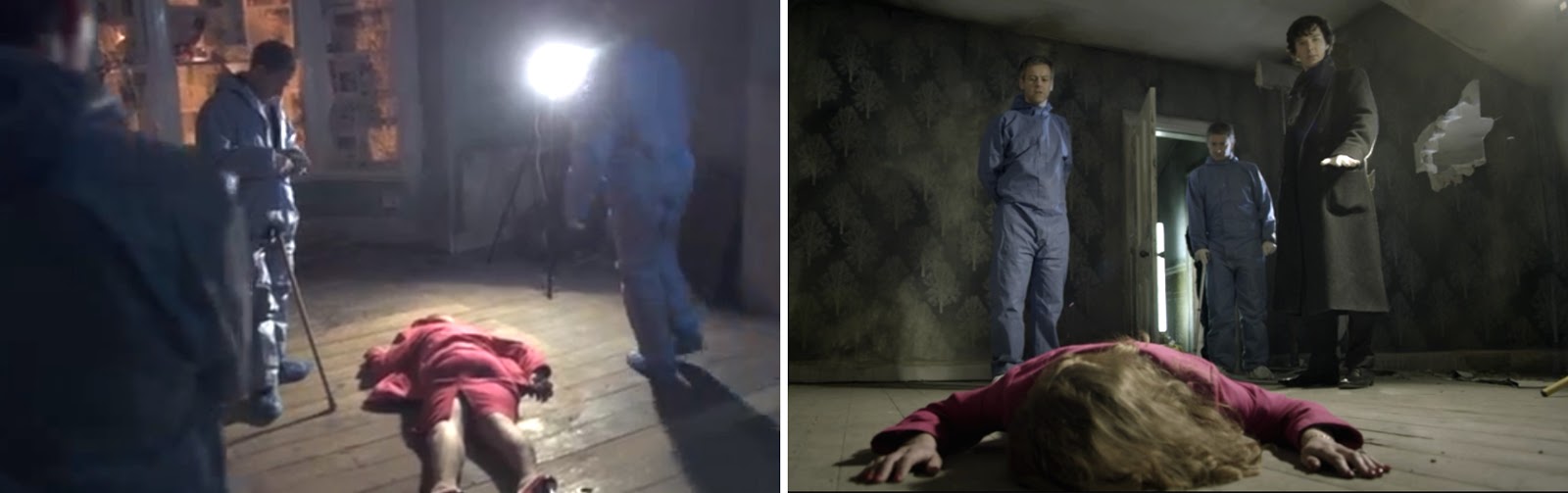

It’s not just Style that shows itself as a value when comparing them both, but how flash and effect can be brought into a narrative as a tool for driving it and communicating point of view. We see what Sherlock sees in words across the objects he observes in the new one akin to his love of texting. We feel the almost insect like rapid fire thought process from within his character whereas in the first version, it’s all observational from the outside. The former may be more natural, but as Sherlock is a fairly prickly if not disagreeable person, seeing him only from without undermines the essential need to empathize with him that getting a brief visual cue to walk in his shoes here and there delivers. There are moments of significant change to the dialogue- especially in the scene above where Watson’s presence is justified by Inspector Lastrade’s refusal to be Sherlock’s note-taker- Watson steps in and his purpose is set. In the new version Sherlock encourages Watson to go further and examine the body after heartily defending his presence for reasons we don’t know. We know Sherlock needs him there, but he won’t say why. Watson then proves his purpose and underscores value in the room and reenforces this for his whole larger purpose in two swift exchanges. Above the first scene the woman is an object observed from a distance, in the latter it’s a person they come to. We see her from her vantage and humanize her where the other objectifies her. Simple stuff of choosing where to put the camera like this can mean the world in terms of narrative meaning.

Here above we see the two new partners discussing how Sherlock managed to derive so much supposedly private information from a mere glance. In the first we see them in a car with a clumsy greenscreen of the city through the rear window behind them as Sherlock ticks off the clues. The dialogue remains identical but in the latter, we’re constantly in and out of the car at key moments. When out, Watson is looking outward as if realizing he’s trapped in a bottle with a scary stranger he also admires. he doesn’t look at us pleading for escape, and so we are left to leave him where he clearly wishes to be. We get a sense of place and motion, of context rather than mere background. And all of it delivered by simple visual choices without changing a word of script. The latter showcases every image as a considered choice. The former leans more on typical and lazy conventions delivering words but not fortifying in meaning. The former is like 1980’s tv still shrugging under its 60 year old vaudevillian heritage, the latter is comics done exceptionally well.

The changes aren’t just the fashion of how they’re shot, they are while watching it unfold night and day different despite the near identical script. It is a case study in choices and corrections that mirror most editorial processes, and reaches well beyond what one editor might do in the bay, and what another could bring. Each change is wholly a storytelling change. Often one that combines or adds narrative purposes to a given scene. Wherein the former may simply show our two characters in a setting as below, the second does it but adds the narrative element of the window to also show us what SHerlock is really there to witness easily and in a way that allows Watson to participate.

I’ve always loved the idea of crafting a short story in which we then find five different artists to interpret from the script and see what each bring. It’s an opportunity to spot, define and understand what makes us each different in how we see and present our narrative material. This side by side comparison of Sherlock is one of the deeply rare and precious opportunities to see that unfold. I cannot recommend studying these two enough keeping in mind one’s own choices and changes. You’ll be a better storyteller from doing it and really when it gets down to it, that’s what we all are at our most basic no matter what form of trade we practice: storytellers.

You can find the final version just about anyplace, but will have to do some mild hunting to track down the unaired pilot via the use of the interwebs. I’d post links to ease your hunting but then I’d be encouraging copyright bending sites that get harry. But do the work at finding it. it’s fairly easy to track down and more than worth doing so.

Fascinating. I had no idea there was an unaired pilot. I'll have to try and watch both side by side.

My jaw may have dropped a little to see my most favorite subject on Muddy Colors. I've spent way too much of my free time discussing Sherlock, and its most excellent cinematography with like-minded nerds on the internet, and it was fabulous to see another take on the pilot/unaired pilot differences. One thing I find interesting is how much breathing room Sherlock is given on so many of the pilot episode. So many shots (like the cabby scene across the table) the directorial choice seems to be over and over again to back up the shot by 5-10 feet. It definitely takes the intimacy between SH and the viewer down a few notches, and I think makes him a more mysterious figure throughout.

Minor points of interest; the unaired pilot is 60 minutes, the final episodes now run 90, you can find the unaired pilot as a DVD extra for the S1 DVD set if you are really curious and don't want to participate in piracy, and, most importantly, they decided to not have Sherlock Holmes wear jeans like he did in the unaired pilot. JEANS!