This makes sense.

Doesn’t it?…

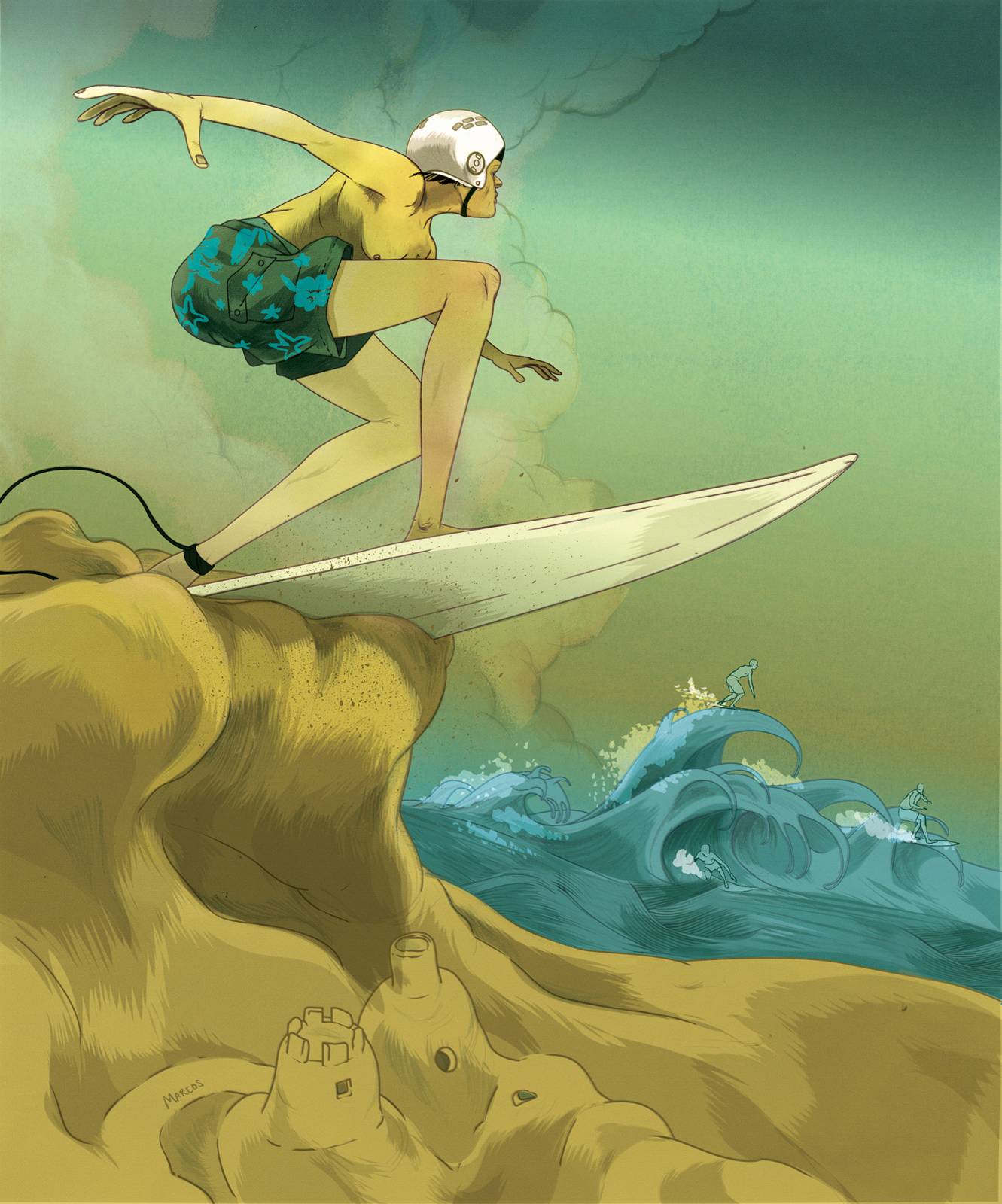

… Because if you distill what’s truly happening when you’re working on a creative project, it’s that you’re forming a relationship with the thing in front of you. It’s relational, and reciprocal: I give to it, and it gives back. There are good moments when you’re flowing and in sync with one another, and then there are also those times that feel challenging, in which you begin to question what you’re doing, and if it’s even worth staying the course. In forging a healthy relationship with your project, communication and honesty is the key. Like many relationships it can begin with a honeymoon period that has a kind of new relationship energy (NRE), or as Don Kelley and Daryl Conner’s “Emotional Cycle of Change” (which I read via the comic artist Jessica Abel’s blog) calls it “uninformed optimism (aka this is going to be awesome!)” This is when both parties are on a dopamine high, when love is palpable, sex is fantastic and occurs often, and the world is seen through the lens of your favourite Instagram filter.

And who knows how long this NRE will last. But like most things, what goes up must come down. The energy settles, familiarity sets in, and the excitement of newness begins to lessen. Now, the real work begins — the tedious, mundane and massive amount of work that is necessary to support the project until completion… or maybe things feel so bad that you choose to break up.

… or quit.

Jessica Abel beautifully outlines the highs, lows and questionable spaces that one might find themselves in during their creative process and the feelings that arise when you think you might want to quit. In her blog she talks about The Dark Forest, the space where you’re overcome with challenges and are in over your head. I’d encourage you to read and also take a listen to her podcast about The Dark Forest.

Ask “Why” Questions

When I’m in this space even though my stomach churns and my body tells me to run, I stay and persist. I try to figure things out, organize, come up with new solutions, and rebuild my relationship with the project or person that’s in front of me because I know when I’m scared, my limbic system kicks in (my lizard brain which is responsible for emotions like love and fear) and it makes me react to stressful situations in a less sensible, more primal way (i.e. fight, flight, freeze). As a result, I don’t always make the best decisions in those moments (I’m the type of person who hits back, runs away, and curses when he feels threatened; surprise to those who have never seen this side of me!) because my brain’s main job is to protect me, whether or not the stressful moment I’m in is dangerous. Let’s use my picture book dummy as an example. I’ve been working on this for about a year, and it’s gone through several iterations. At the beginning I had so much gusto, but I’m now in a spot where I feel frustrated; all parts of the story are being interrogated: the structure of the story, the intention of the characters, how the illustrations look — everything about it looks and feels different than when I first began, the new relationship energy I had with it is gone, and to be honest I want to throw in the towel… and I hear myself asking this question over and over again,

“What am I doing?

… Why don’t I stop, run away… press delete?

But this is the wrong question to ask.

Instead of “What am I doing?” I should be asking “Why am I doing this?”

I hate why questions because it forces me to dig to the core of whatever it is that I’m unsure about. Once I know what my true intention is then I can direct my actions in a more deliberate way. I flounder less, I’m more decisive, and I have a higher degree of commitment because I know that what lies on the other side will be worth it. Although persistence doesn’t guarantee success, in my experience knowing the purpose of why I’m doing something, and to understand the weight and value of it, makes the process feel more grounding and gratifying.

Why, Why, and Why Again…

Just beneath the surface of a why question lies an easy answer, one that’s predictable and automatic. For example,

(Q) Why am I doing this?

(A) Because it’s fun!

Words like fun, boring, and cool are lazy and thoughtless ways of describing things; they’re flimsy and meaningless – especially in this type of situation. An answer that I would consider and accept is one that is more specific to the project in question. The way to get to the real answer is to ask yourself this question again, “Why?” and to come up with a more precise answer . So again,

(Q) Why am I doing this?

(A) Because I want to make a picture book of my own – I want to illustrate and write it.

This still isn’t a good enough reason, but I’m getting warmer because answering this way makes my belly churn and tighten (I’ll explain more about my belly truth detector later).

(Q) Why do you want to illustrate and write this book?

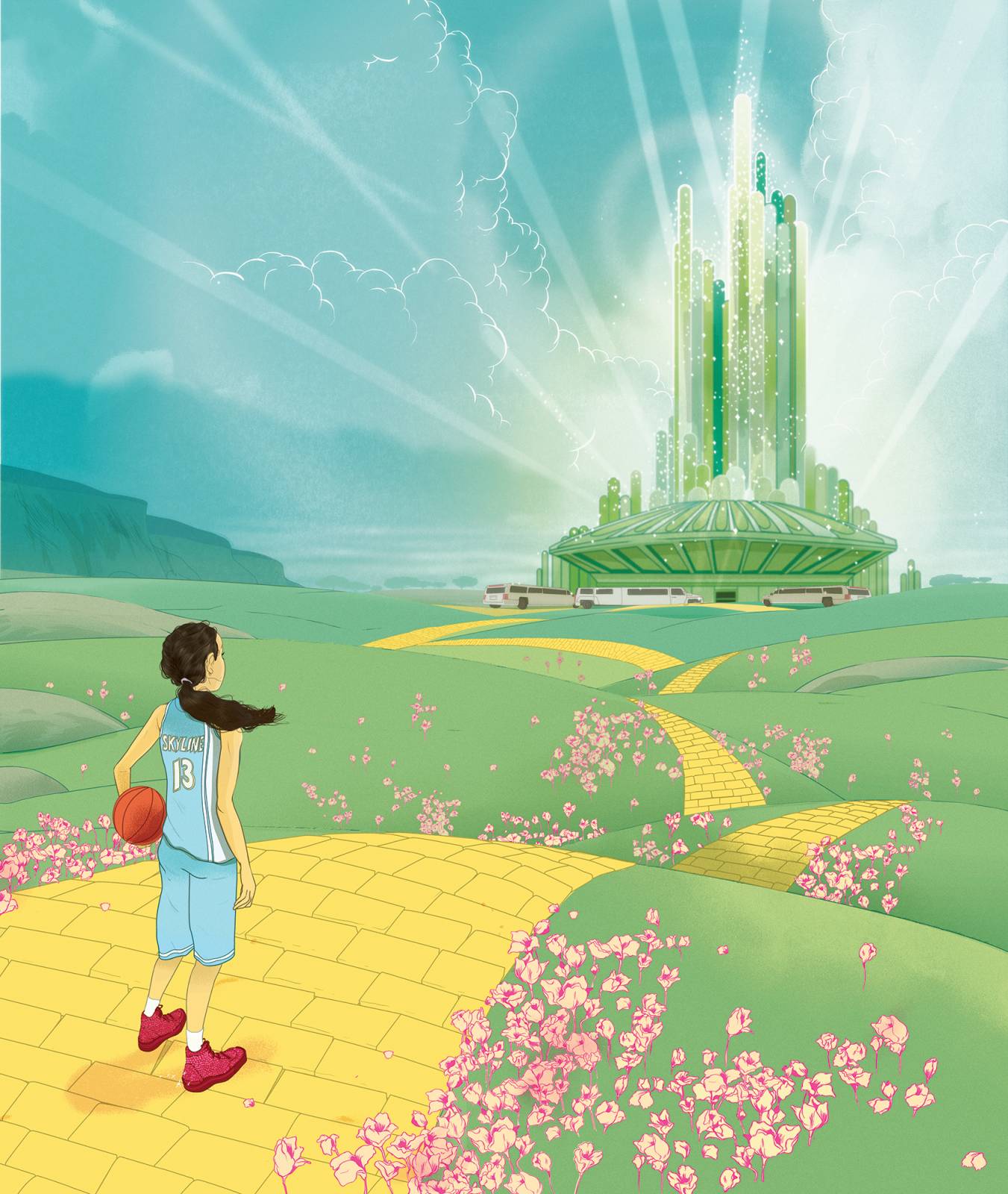

(A) Because through my own research I’ve found there are hardly any books that tell the kind of story I want to tell (the one I’m telling in my book dummy)… and that many of the protagonists I see in Kids Lit don’t reflect the child version of me.

Okay, so you do feel strongly about this project. It’s meaningful to you and the reason why you’re doing this goes deeper than awards, money, and fame. So, here’s another why question.

(Q) Why do you want to quit?

(A) Because I’m frustrated, and I’m tired.

(Q) Why do you want to quit?

(A) Because I’ve sunk so much time into this project?

(Q) Why do you want to quit?

(A) Because the feedback I received from agents and publishers was negative.

(Q) Why do those comments make you want to quit?

(A) Because they hurt my feelings; I feel rejected – like I don’t belong.

Bingo!

Making A Decision Using Your Three Brains.

The reason for asking why questions over and over again is because it brings me closer to the truth. I believe my first few responses to this question is kind of like picking at the surface of something. The more I scrape away at it, it eventually begins to crumble and reveals what’s underneath. Although I might have an immediate answer to that why question, it’s probably not one that’s well considered. It’s similar to asking a person “how they’re doing?” their response is usually “fine,” a programmed, superficial, and civilized response. I could’ve gone even deeper with my questioning and asked ones that are tangential to “why” such as ones related to money and opportunity cost. For example,

“How much money did I spend on this project?”

“Hows does working on this project take time away from my commercial work and how does it negatively impact my life?”

But I chose not to because it wasn’t costing me anything and I was working on this project during “off-hours”. In business, the term is called sunk cost fallacy, which means that the more time, effort, money, and investment that you pour into something, the harder it is to let go of it. We’ve all been there before.

Since the answer to my question, “Why do the agents’ and publishers’ comments make you want to quit?” made me feel uncomfortable, I knew this was a good place to pause, examine the situation and hopefully come up with a decision.

Do I persist and try to find new solutions?

Or do I quit?

Here’s where I talk about my belly truth detector. My gut knows when I’m telling the truth and when I’m not. For example, if I ask myself a question and come up with reasons that don’t (emotionally) move me in any way, or which don’t allow me to feel the answer then I know my decision at that moment is incorrect and untrue. For me, it’s not enough to do something only because it’s logical, what’s more important is to evaluate this logic alongside the feelings that this decision stirs up in my body. I’ve said to my students in the past that as artists we have three brains: one in our head, which analyzes and examines, one in our stomach which feels for an answer, and the third is in our heart which marries the two. I understand how silly this sounds, that it’s incredibly woo-woo, and can’t be measured, but I call this blend of mind and body decision making, my intuition; it’s emotional data that I use to inform the steps I choose to take in every part of my life. So far, it hasn’t failed me.

Ultimately, I decided that I didn’t want to quit making my picture book because at the end of the day, my choice to almost quit wasn’t because I didn’t enjoy the process of working on it, or because I thought the idea was stupid. Almost quitting uncovered feelings of rejection, of not feeling accepted, and unworthiness. These reasons are rooted entirely in my own ego, and because of this, I felt it wasn’t a good enough reason to stop.

More About Uncertainty. It’s Okay To Change Your Mind. Quitting Isn’t A Bad Thing.

When I’m in the throes of uncertainty, and fear as it relates to my art, I equate this with being stuck. My creative process feels like I’m running on the spot; I’m moving, but I’m not going anywhere. I tell myself that my job at this point, is to figure out how to get back into the flow of things. In the past, I’d use words like kick ass, kill it, or slay, but I don’t anymore. I believe that words have power, not in an incantatory way, but the words I choose to use influences the way I present myself, and in turn how I’m received by others. The meaning that I place onto these words mobilizes me in a productive way, it informs the way in which I work, and how I approach problem solving. I don’t try to battle my problems muscularly anymore, instead I choose to slow down and walk alongside them, all the while thinking things through.

Culturally, I believe we’ve been trained to finish what we’ve started; that if we don’t, then we’ve failed.

I don’t believe this.

Sometimes quitting is about the work that you do up to that point. It’s a gathering of information, and the building up of knowledge, skills, and experience that one needs to get closer to being able to make that thing, or achieve that goal the next time. Coming close to your limits, or being close to failure allows you to see how much farther you need to stretch in order to succeed. It provides a more expansive and deeper understanding of the environment within which you’re working; both the positive and negative aspects of the experience when weighed side-by-side, create perspective. It makes the process feel less scary and your goal more attainable the second, third, fourth, or even fifth time around.

Share Your Work. Get Feedback. Do The Work. Ask For Help.

So how do you know if your project is truly worth pursuing? In my case, a few publishers have already rejected my current picture book dummy, and about fifteen agents haven’t had many positive things to say about it either. They’re the professionals so why not listen to them, throw it away and start over? Considering the larger picture, I know listening to a small number of people isn’t always a reliable indicator of whether to stop or continue (there are countless stories of successful individuals who’ve experienced a wild number of rejections before becoming successful. Look at Seth Godin the writer and marketer who received 900 rejection letters in a row). Fortunately, what I did receive from some of these individuals was critical feedback that I could apply towards my revision process.

As artists we have a level of taste that isn’t always matched by our skills, as Ira Glass puts it in his talk about how to succeed at making creative work,

“Nobody tells […] people who are beginners that the first couple of years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer… It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close the gap (between taste and talent) and your work will be as good as your ambitions.”

I know where I sit in the picture book industry as an illustrator, and as a writer. I’m a newbie, and even though I’ve been illustrating professionally for seventeen years, within the picture book industry my experience represents only a fraction of that. Still, I trust that my taste is above average. However, because I don’t have the level of skill to deconstruct and critique my work in this genre (I’m still learning about the structure of storytelling) I’ve decided to ask for help from people close to me whose taste, talent, experience, and opinions I trust; those who I believe are superior in their respective industries, and can give me critical feedback in a compassionate way. And so, this is where I’m currently at. Now I have notes on how I can edit my book; how to make it better – I still haven’t applied them yet, but I will. There have been countless times when I’ve wanted to quit. Even though I’ve heard many “No’s” from industry gatekeepers, I don’t see them as absolute, at least not yet… A “No” from them isn’t a “No, forever,” it means a “No, for now.”

Recent Comments