I love a series, and this is one I’ve been thinking of starting for a while. We are all guilty of looking backward at Master Artists of the past and measure ourselves against them. However, we always compare where we are (at the beginning or middle of our careers) to where they were at the height (or end) of their career – we never really take the time to spread out that artist’s career and look at how it developed, and compare where we are to where they were at the same stage. We also rarely take into account the fame they had when they were alive, or even right after their death – we always consider them as the master we think of them as in modern times. There are many master-level artists history has forgotten, and many artists that were only considered masters long after their death…usually because another group of artists rescued them from obscurity when they got famous (like Botticelli being “rescued” by the Pre-Raphaelites, but we’ll save that for a future post).

When I give career advice to artists at the beginning of their career I encourage them to do two things: 1) look at living artists they admire, and go backwards a few years (very easy now with website archives and social media and podcast interviews) to see where they started and how they got from there to the present, taking into account not only their work, but also the clients they worked for, awards they won, etc. (I call this “career-stalking”) and 2) make sure you don’t only take inspiration from artists years ahead of them, make sure you career-stalk artists just a stage or two ahead, because it is much easier to see their careers develop in real time. It’s much easier to see turning points happen as they happen or a year or two later, and much harder to see it in artists decades or centuries dead.

That’s why I am starting this series: to remind us all that even Masters struggle, and it’s a mix of both hard work and coincidence (you can call it luck) that makes a Master Artist that history remembers.

Today’s Turning Point is a look at Alphonse Mucha and the lucky break that made his career.

I knew this story but was reminded of it recently by a fabulous talk the Chief Curator of the Poster House Museum, Angelina Lippert, gave in conjunction with the Poster House exhibition on Alphonse Mucha. It was a fabulous exhibit and I encourage you to check out the archive online. I’ll be quoting from the writeup. Also do yourself a favor and follow them on instagram – Angelina has been doing a fantastic job in quarantine of showing collection pieces and giving lots of virtual talks and even poster history happy hours (I’ve gone to the Amaro one and the Absinthe one, both fabulous).

(In fact, if you read this article the week it posts, you can catch Angelina giving this talk again for the New York Public Library on August 17th for free. Highly recommend!)

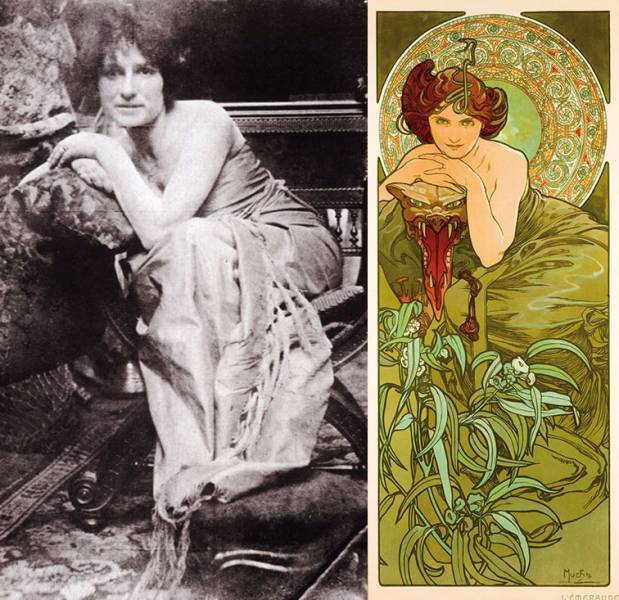

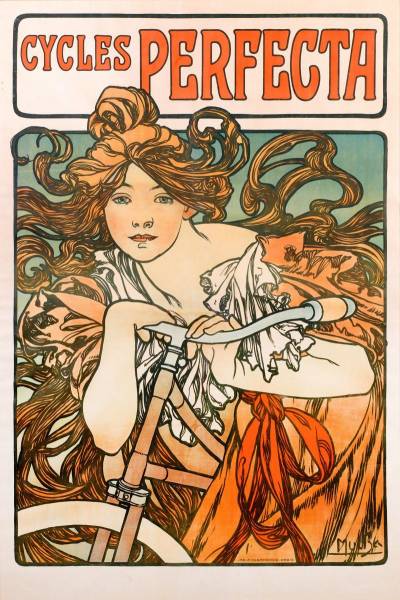

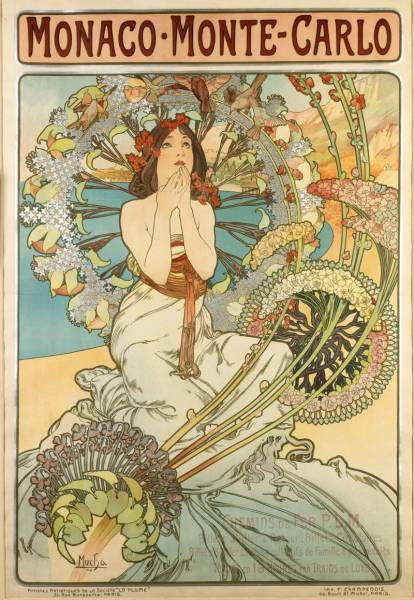

Anyway, back to the story. We think of Mucha as the absolute master of Art Nouveau. He was one of the first artists that really worked in both celebrity and corporate branding. His poster for Lu cookies featuring Sarah Bernhardt was actually the first celebrity endorsement ad. Then he went back to his homeland after the formation of the Czech Republic and pretty much branded the country, designing stamps, money, municipal buildings, and honestly a good chunk of the city of Prague. I have a tattoo inspired by an Art Nouveau poster by another artist, and everyone just asks to see my Mucha tattoo. He is one of the artist names that even non-artists know. Honestly, he’s so popular that it’s kind of a cliché to see a print of his art, kind of the same status as seeing a Van Gogh or a Monet print in someone’s apartment.

But did you know he was considered a “failed artist” all the way up until he was 34 years old? He was Paul Gaugin’s roommate…do you know how hard it must have been to struggle under the same roof and while being friends with the entire Paris circle of very popular impressionists and other illustrators of the time? It got so grim that in 1894 Mucha didn’t have enough money to get out of Paris for the Christmas holidays and either visit family or go to the countryside with his more successful friends. Another artist asked him, since he was staying in town, could he maybe go on-press for him to make sure the colors on his poster design came out ok. I imagine it must have been an awkward conversation. Hey Alphonse, you can’t afford to go anyplace nice, can you make sure my poster comes out ok, I’ll give you a few francs…

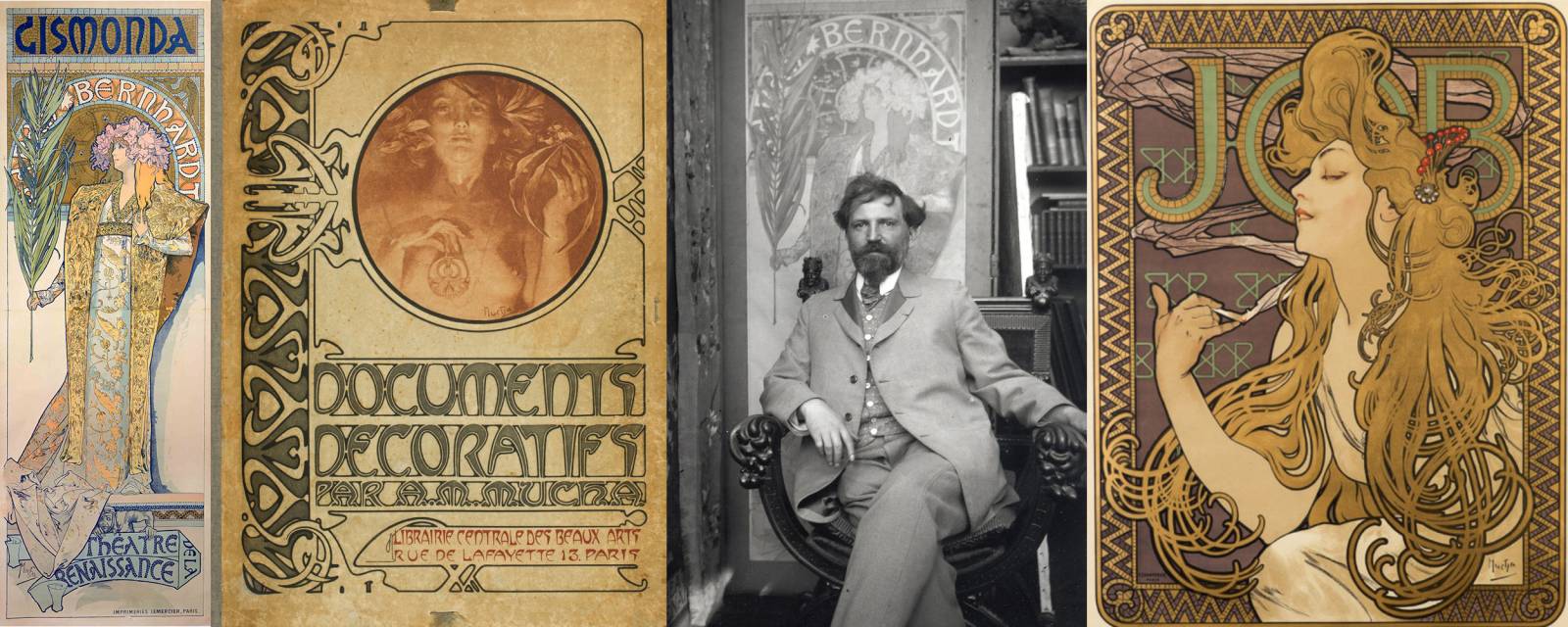

Luckily for him, Mucha did it. I like to think he was a good pal, but maybe he just needed the money. Regardless he was at the Lemercier printing house when a rush job came in. Sarah Bernhardt’s new play, Gismonda, wasn’t selling enough tickets, and the theater owner thought a snazzy poster might help sales. Unfortunately all the top illustrators in Paris were out of town, and Mucha threw himself at the job. And almost blew it – the theater wanted a simple bold poster like the style that was popular at the time – certainly not the overly intricate one Mucha delivered. The printer didn’t want to show it to the theater and the theater didn’t want to use it. But luckily Sarah Bernhardt (a lady very savvy about personal branding and marketing) saw it and loved how different it was. She took a chance on it standing out from one the poster-layered walls of Paris and made them print it. And it was a hit! They had to reprint the poster to sell to individuals who wanted a clean print. And the play became a hit as well.

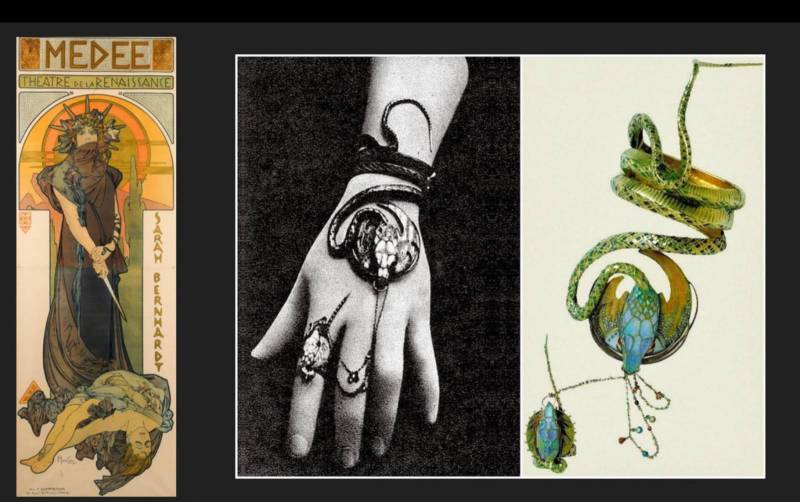

Mucha’s Gismonda poster. Not only was it was more intricate than other posters at the time, it was also a weird size, used metallic inks, and was way harder to accurately register on press.

After that Mucha became Sarah Bernhardt’s personal artist, and they worked together to change both celebrity and advertising ever after. The entire concept of “aspirational advertising” was born, for better or worse. Though I honestly wouldn’t mind as much if the artwork on all ads was as gorgeous as art nouveau posters!

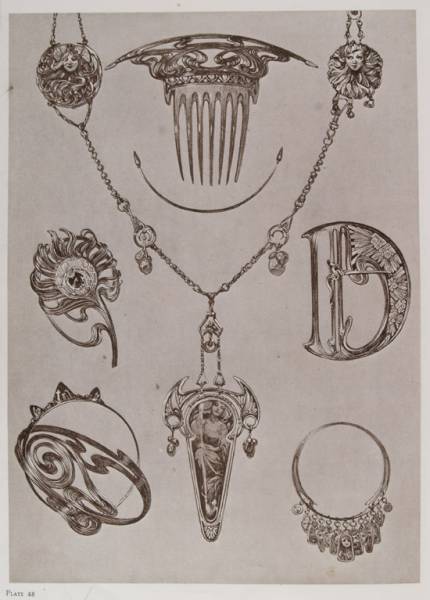

Bernhardt loved Mucha’s designs so much that when he designed this bracelet for the Medea poster she had it made to wear in the show.

I’d really love to say that Mucha had it made after that, and he did as far as fame went, but he ran into some financial hurdles. Back then the artist worked for the printer and was paid a flat fee, so no matter how successful the posters were, Mucha could only make so many, and raise his rate per poster so high without pricing himself out of work. On top of this, the printer often re-used the same art for different clients, and the printer would hire other artists to redo the type and even do alterations to Mucha’s art. (Just in case you thought Work For Hire clauses were a new phenomenon)

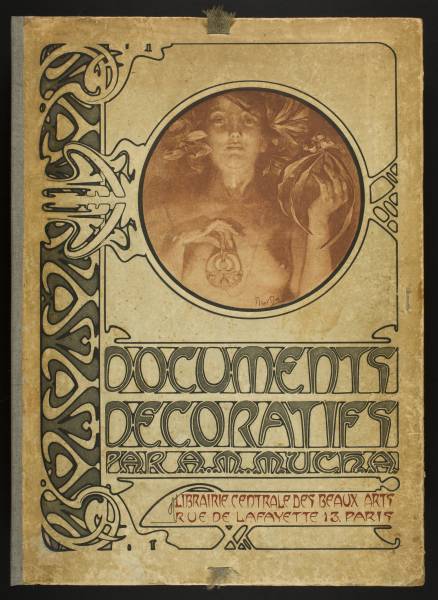

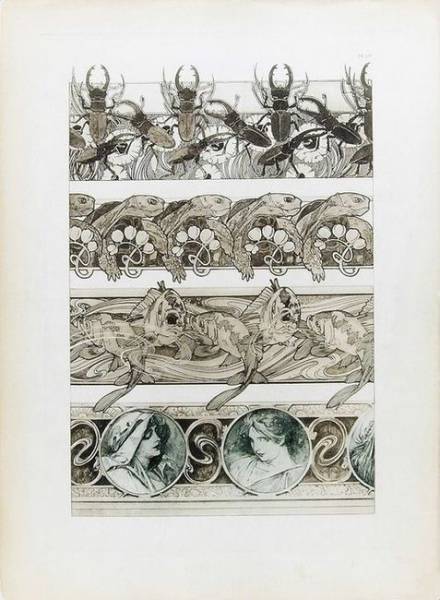

Mucha actually went to his patroness and genius businesslady Sarah Bernhardt for advice. They did 2 things: 1) they decamped to America to play in bigger theaters for bigger audiences and Mucha became even more popular, and 2) Mucha created the Documents Decoratifs, which was a catalog of mix and match Mucha art that other printers and artists could use to make Mucha-style postes with. And the money went into his pocket for a change. It’s also the point that Mucha’s style overcame pretty much every other artist and became what we think about when someone says Art Nouveau.

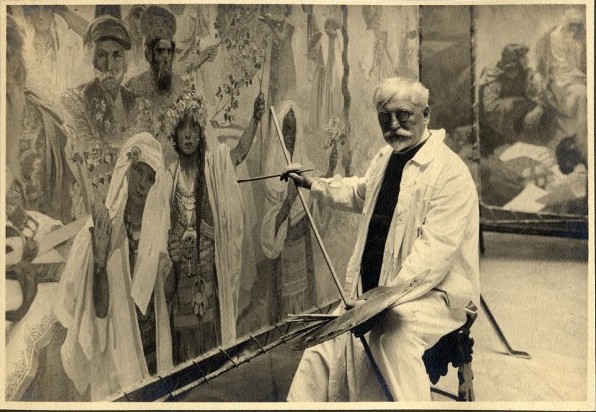

After that, there was some issues in America, and Mucha ended up teaching at the Art Institute of Chicago for a while. Then he went back to Prague and did a ton of work for the Czech government (very prestigious but government work never pays well) and ended up creating the masterwork series the Slav Epic and gifted it to the Czech people. Unfortunately things started going downhill in Eastern Europe when the Nazis came to power and Mucha died after being interrogated (a.k.a. tortured) by the Nazis in 1939.

I got a chance to go to Prague and take myself on a bit of a Mucha tour, including the Slav Epic, and it was staggering. If we’re ever allowed to travel again, I highly recommend it as a worthwhile artist’s pilgrimmage.

Is Mucha a Master Artist? Absolutely. Does that mean he didn’t struggle? Hell no. He was 34 before he got his breakthrough piece. He struggled endlessly with the business end of things, even when he was massively popular. And then the incredible artistic gifts he left to his homeland and his people were squabbled over and underappreciated for years.

In fact, even though Mucha was incredibly famous in his day, his work had faded into obscurity until one day in 1963 the Victoria & Albert Museum in London needed a cheap and easy exhibit to fill a hole in scheduling, and that meant digging something out of the archives they already owned. A curator found a bunch of Mucha posters, figured they’d serve, put on an exhibit, and single-handedly kickstarted the 1960s art nouveau revival/psychedelic poster movement, making Mucha a star all over again. Where would poster history be without that scheduling quirk?

I want you all to remember that no artist has it “easy” – we all struggle. Some of us struggle with different things, at different times, but we all get our share. And I’m not trying to glorify the struggling either – if you have read my articles before you know I do not believe in the myth of the Starving Artist or that we are better artists in proportion to the amount of suffering we do. But I want you all to remember that just because you are struggling doesn’t mean you are less of an artist. It doesn’t mean that one day you could be doing a favor for a friend when you’re down on your luck and it can’t all turn around. No Master gets to be a master without a hell of a lot of hard work, and a hell of a lot of luck on top. The hard work puts you in the path of the luck. Most of all, be compassionate with yourselves, and other artists on the same road. Help each other, because we’re all struggling, even if (especially if) you can’t see it from the outside. Hard Work + Luck + Struggle + Compassion will get us through.

Well crafted review… I had read much of this, but your retelling made all of this sound anew… Thanks!

My pleasure!

Bravo!

Thanks for this. It’s always nice to be reminded that even the “big guys” struggled.

Exactly. Wait till next month when we talk about Botticelli!

The Slav Epic alone is worth a trip to the Czech Republic. I saw it in Prague in September 2016 when it was at the National Gallery-Trade Fair Palace, and it was well worth the time. Simply stunning, immersive, beautiful work and on such massive scale.

We spent a several hours at the exhibit alone, but I’d also recommend checking out the museum at the Trade Fair Palace. We had to kill some time before we could get in to the Slav Epic, and while the Trade Fair Palace looks like an ugly government office building on the outside, the exhibits on the inside are incredible. There was so much art that would fit here at Muddy Colors, it was a real wonder.

The last I heard about the Slav Epic, it moved to Moravský Krumlov, about an hour from Brno. Opened in July and supposed to be there for 5 years, until Prague builds a permanent space for it in the city.

I was lucky enough to see it in Prague a few years ago when they were holding it in one of the art museums. Made a trip just to see it while it was easier. Worth every penny. I walked out of the gallery literally art drunk, and one of the security guards had me sit down for a minute and make sure I was ok. Lol, I guess they were getting that a lot!

I went to Europe just to see the Slav Epic! Your retelling of the story brings be right back there.

I had a chance to see the Slav Epic (or most of it as 2 of the massive paintings were undergoing restoration) at the Obečni Dum in Prague while it was on display a few years ago, and toured the Mucha Museum, seeing the ginormous Gismonda posters in various stages of printing and it was an experience I will never forget. I know a private foundation is still working at raising the funds to build a site to house the Slav Epic since it doesn’t have an official permanent home. While there is more of Mucha’s work in Paris than Prague, nothing will ever beat standing in the Lord Mayor’s Hall knowing Mucha painted every square inch of that room. Thank you for the great review and the perspective required to look at influencial artists before they were a household name.

I know, and the Municipal Building/Opera House too! I fell in absolute love with that building.

Brilliant.

<3 thanks

Thank you for this needed reminder. Almost a year ago, I took the pilgrimage to Czechia for this very reason. Unfortunately the Slav Epics were in Japan, but I was able to see the museum and his beautiful city, buildings, and countryside. I definitely spent hours in the tiny museum, soaking up everything I could. The Medea snake bracelet story is brilliant and who doesn’t want that killer bracelet. I also love that they had a hard time keeping the Gismonda poster on the walls in Paris, since they were often stolen and sold for a markup because of how much they were loved.

Excellent article!

Great article!

Did you know the snake bracelet (actually made by jeweler Georges Fouquet from Mucha’s design) wound up in the hands of the legendary Marlene Dietrich decades after Sarah Bernhardt’s death?

This article has some fascinating details about the creation and later fate of the bracelet:

https://medium.com/@tvmartinez/the-serpentine-journey-of-an-iconic-art-nouveau-jewel-3b6a16c4ddf7

I envy anyone who’s been able to see the Slav Epic in person– the best I’ve managed to see in person of Mucha’s work has been a few posters and one of the versions of the bust “Nature.”

Awesome thank you!

A mini vacation to read this piece after working a goat farm world. My bucket list is to go to a museum. I am 3 hrs from N.O. La. Any suggestions are very welcome.

Well, I think it’ll be a long time until we’re taking long trips to any museums, but in the meantime a lot of museums are having great online programs! I definitely recommend The Morgan Library’s free online videos (they just had a fantastic exhibit on Sargent’s charcoal portraits) https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/john-singer-sargent

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has been posting a lot of online talks and tours as well: https://www.youtube.com/user/metmuseum

Thanks for putting this all together, Lauren. Here’s a link to free pages of the Documents Decoratifs: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Documents_Decoratifs_(1901) I’ve always wanted to add some art nouveau elements to some of my work!

Thanks!

Thank you for this; it’s a helpful change in my perspective.

Thank you!

Thanks for that my dear fellas!