One of my favorite things to do on a blustery, cold day in February is to watch the Winter Olympics and paint.

Sadly, it only comes once every four years. Yet, the 2022 Beijing Olympics reminded me once again what it takes to become an athlete of such high caliber: complete and utter focus of attention on the goal.

That’s how an olympic athlete learns to get better and refines their skills. It is a daily endeavor to keep their mind on the task, to keep their efforts in the most efficient learning mode possible. To stay at their peak each and every time they train.

That’s the key word: train. Olympic athletes don’t practice, they train. There’s a difference. Practice is about going through the motions, while training is about a concerted effort to learn as you go. That effort is tied to getting one’s mind in a condition of attention so refined, so sensitive that when a mistake is made, the athlete stops and analyzes, runs through the problem in their mind, visually, chooses a possible path to correct it, then runs through it again. If they run into a problem going forward, they repeat the process. They will do this over and over again until the problem is solved. They will continue training in this way to habituate the corrected method.

When an athlete competes, they are in the most focused mindset that they can achieve. Many athletes have spoken about how much the effort is more mental than physical. That makes the difference in a good or great performance.

It is very much the same with the creative arts. Specifically, painting.

The information seemed to coalesce in my mind: why shouldn’t I try to approach my work with the same effort as an olympian?

Years ago, struggling with my work, confused and frustrated with the lack of attention it was getting, I happened to watch the Olympics. About the same time, I’d been reading the studies of neuroscientists working with performance issues and the human brain. The information seemed to coalesce in my mind: why shouldn’t I try to approach my work with the same effort as an olympian?

Up until that realization, I’d been using what I assumed was the proper way to paint. I did my initial thumbnail sketches, designed and composed the image, gathered reference, and prepared the illustration board or canvas. Then I blissfully filled in the color while listening to music or books or, rarely, watching movies.

But the olympians didn’t do that. They were murderously intent on their tasks. And I wanted that kind of focus. Once I realized that I’d let my head phase out, drift into a comfort zone, I knew what was needed to get better. Constant, unrelenting focus, every time I held a brush.

My career turned a very sharp corner from that time on.

Every painting after those Olympics was created with a mindset of full attention. Peak lucidity. I became aware of the brush in my hand and the amount of paint on the end of the hairs. I was aware of the flow of the pigment, the resistance of the canvas, the pressure of the stroke. Brush shape, brush size. Brush angle. I watched and remembered how the strokes became responses of the brush. What strokes reflected shapes. How much pigment gave me rough broken strokes; how much gave me free-flowing strokes. How to achieve smooth passages and how to break up others. I memorized it all through hours and hours of focused attention across many, many paintings over several years.

During that intense training period I found a voice that became more and more my own. I say ‘a’ voice because I think we all have many voices inside and it’s awkward to try to glean one from the chorus.

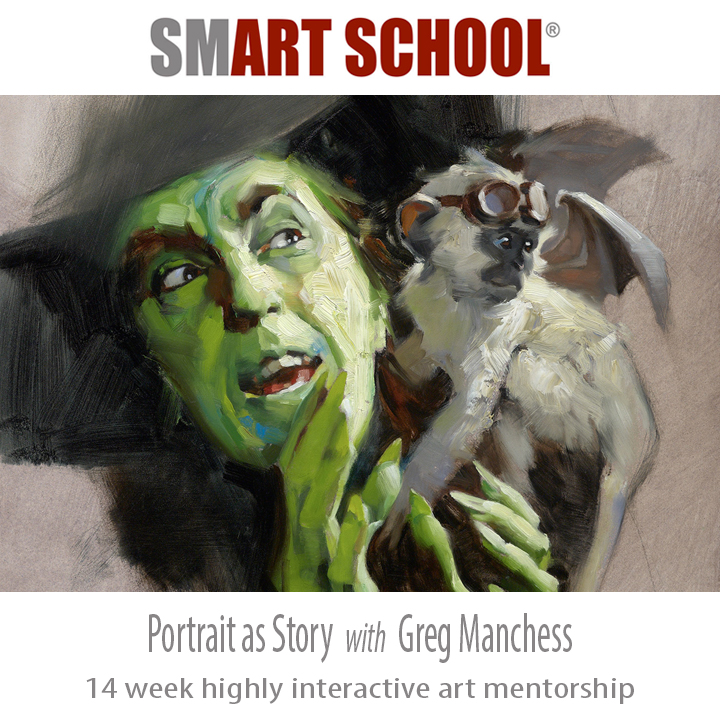

I’m teaching a class in portraiture this Spring semester called, Portrait As Story. When I teach, I approach the potential painter as if they are like me, having the same fears, having the same hesitations, the same disbeliefs. We deal with it in the paint, whether digital or traditional.

The way to get better at painting is to break it down into achievable sections. This is called “chunking” by neuroscientists. Breaking the process apart into feasible chunks, to understand the endeavor, then piece the chunks together.

When we paint, it seems we succeed or fail with every stroke. It feels like each stroke is a test. As new painters, or even as seasoned painters starting a new image, we fail constantly. Nobody puts down perfect strokes each time they touch the surface. So we reapply to correct or ‘fix’ the last application. Paying attention is imperative because sometimes we’re successful and we need to record that success. Most often we’re not and unfortunately our brains record that, too. It would seem logical, even necessary, to record only successful strokes, but there is discovery in the failures as well.

In time, we fail less often and we lay down good strokes. And we do this over and over again until after years of study, they become too perfect. In order to grow, we start to look again for ways to change them. We experiment and attempt to put down awkward strokes, but we’ve spent so much time training to paint well that the strokes won’t suddenly return to neutral, return to zero. We have to force the brain to break with the learned skills. We must ‘unlearn’ to learn anew.

This is why failures are key. This is how we learn.

This is what I teach, and I still train like this today. But now it has become a joy. I understand what it’s like to have survived critical learning failures, reassess and readdress the problems, and then breakthrough to solution. Yet, there’s so much more to learn, so much more to experience.

We learn that there’s no point at which to stop and glide. Sure, we might flow with something for awhile, but the learning is in discovery. This is what the fine artists have been blabbing about for more than one hundred years, but really couldn’t put into absorbable terms. The old idea was to get a style and work it for the rest of one’s career, if one was smart…or lucky. But the actual endeavor is to grow as an artist. To learn, produce, move forward. Sound familiar? It’s basically the same steps as an olympic athlete training to get better.

We’ve come a long way. All of us artists are learning to identify what the creative process entails, what is required, and what is necessary. Yes, we stand on the shoulders of giants, but we reach to exceed both our grasps. We pass that information forward to the next generations who will climb onto our shoulders. And from that process, perhaps we will learn as a species what it means to communicate visually.

That’s a lot to absorb from a cold day in February watching Olympians push to the brink of failure to gain resolution.

Their efforts may seem physical, but their real strength is in their focused attention.

Can’t wait to take your mentorship later this year. Thanks for sharing such a deep insight into your mind!

Hey Zeb! Glad to have you onboard! Will that be for the Fall semester?

I really needed this today Greg. Very inspirational. Can’t wait to learn this from you.

Love to have you in class, Natalie! I think you’re going to love it. You won’t look at your work quite the same way again…