The project I’ve spent the better part of seven years conceiving is finally finished. From the first thumbnail sketch to the weekend before this past Thanksgiving, Above the Timberline has consumed nearly every extra moment of my free time and invaded my actual work time to both overwhelm and inspire me to produce my vision of a future world.

From the beginning, I was warned by many that what I was attempting was not only too much to accomplish, but too grand for a publisher to produce. That things like this only come along once every couple of generations. No one can pay for it. No one understands the format. Why even bother? I was up against a considerably massive wall. Indeed, they may have been right, if it wasn’t for one overriding factor.

I had to see it done.

Sometimes, when the vision is clear and the means are not, we have to make difficult decisions. What do I sacrifice? How badly will I fail? Can I survive?

The pleasure I saw in people’s faces when they saw the original concept painting, and the excitement they had when asking questions about the idea, gave me energy and gently coaxed me into more visions and variations of what I’d started. Each time I talked about it the enthusiasm across their faces to see more, to find out more, was fascinating. And with that I gained more interest in my characters and their world.

1. Thumbnails

Even the very first painting started with two small thumbnails. I followed the one I chose almost religiously because it represented the feeling of the finished painting in its sparse lines and composition. Being able to read-into a suggested image is quite powerful. The brain fills in detail that it needs, and as you’ve experienced too, those tiny sketches have so much power that it’s tough to live up to that vision. But the thumbnail sketch captures your instincts intuitively and mirrors your deep impulses for creating an image.

That’s where I started for the entire story. I sat over many mochas and hot chocolates and tea in coffee shops across the US, drawing postage stamp size sketches, building the story from images, one after the other. Pages and pages of stacked thumbnails become my codex which I followed for as long as I could until something bigger or better started squeezing into the mix and I found myself expanding the story line.

When the visions slowed down, I went to writing. The writing gave me more images. So when the writing slowed down, I went back to sketching. Furiously at times, and contemplative at others. Characters came and went, situations were established and abandoned, and all the while I learned more and more about my main character, Wesley Singleton.

2. Preparation

The manuscript had to be finished first. I had to have a practical sense of how long the story would be, and find out from the editor, once the book idea was sold, how many pages I would have. This dictated how the story should flow. I had to start with the end in mind, as they say.

I basically wrote a three hundred page novel, learning my characters and their backstories, and finding what scenes to keep and what to let go. Then I severely cut the whole thing down to about 30K words. I clipped and trimmed, shortened and discarded, and was left with only what I most wanted to pursue, express, and paint.

Now it was in a more streamlined format and this made it much easier to link up with the images. Of course there were more changes as the words and pictures came together to form a visual through line of story. At this point, I drew larger double page sketches and dropped copy into each layout to see how it would fit.

3. Reference and Research

I’d been looking at polar images for many years and had some initial ideas about how my ice world would look. I flipped through books, magazines, scrap files, inspiring image folders and let all of it wash over me. I had read countless books about the arctic, high mountains, winter, snow, ice; books about writing, books about thrillers, mysteries, science fiction, science, cinematography, graphic novels; books about survival, weather, animals, landscape…even an entire book about the snowball planet theory, which I thought I had originated, but discovered scientists have been contemplating the idea for some time.

One of the best places I found for copyright free images was Dreamstime. They have quite an extensive library of all types of subjects, and no shortage of snowy mountains and scenes to help me visualize. Quite inexpensive as well. I was up to my eyeballs in polar bear reference, much I’d shot at zoos, and rather quickly learned to draw them to fit my situations.

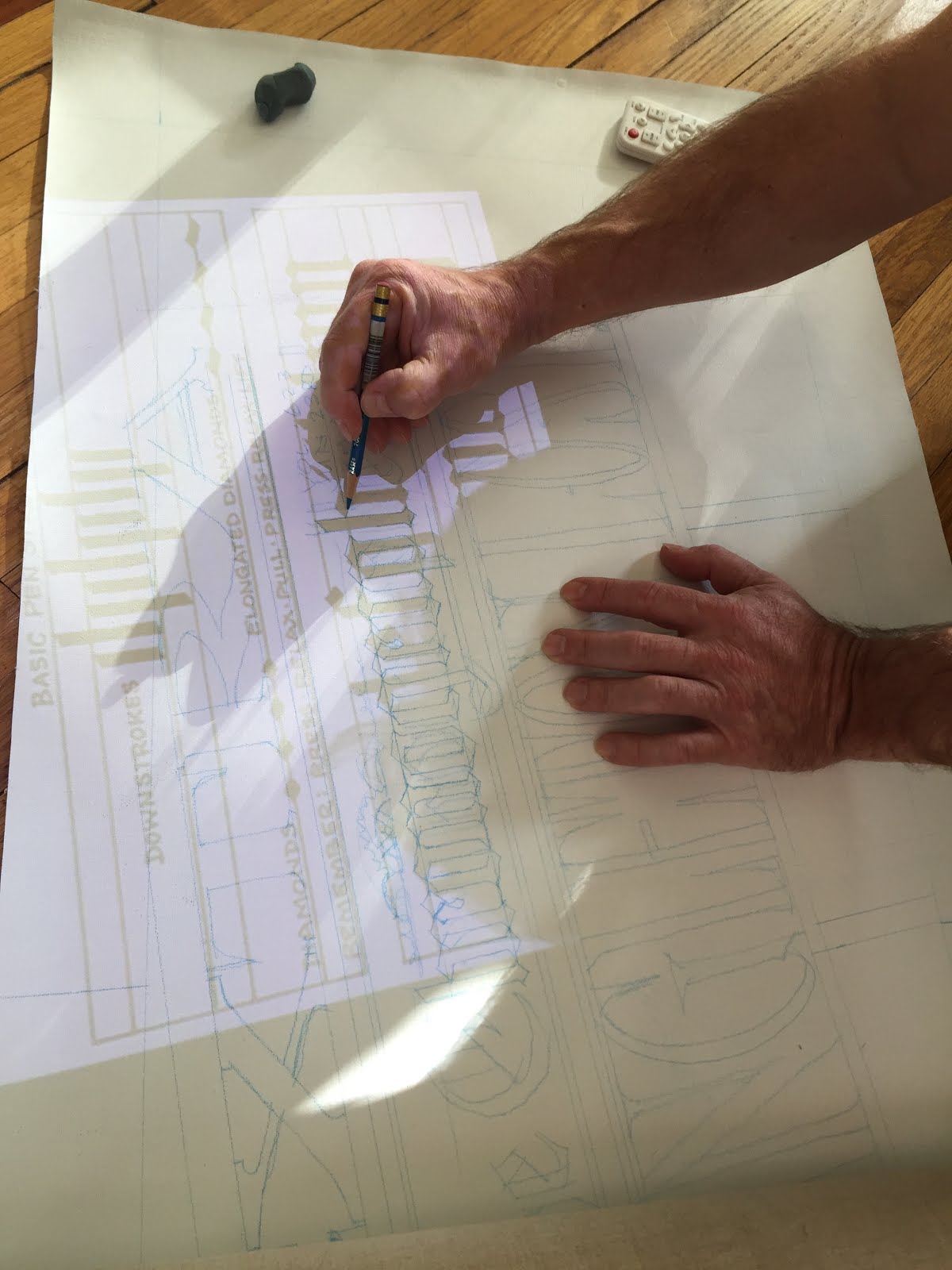

4. Drawing

There is just no substitute for good drawing. I found so many times that I had to redraw from the reference for my images to make sense. After a few weeks, projecting reference became tedious and slowed me down. I learned to trust my drawing instincts and let any distortion occur naturally. I finally learned that getting it right means making it believable, not actual.

I had known this from many years of freelance illustration, but in this context, I had to learn it all over again. I had started with the idea that I wanted it all to flow. The best way I discovered to do that was to let all the reference flow through me first, filtered through my sensibilities, and let it become my own.

You’ll learn this, too, if you haven’t already, but I know for certain now that one hundred twenty-two finished paintings will be your best educator.

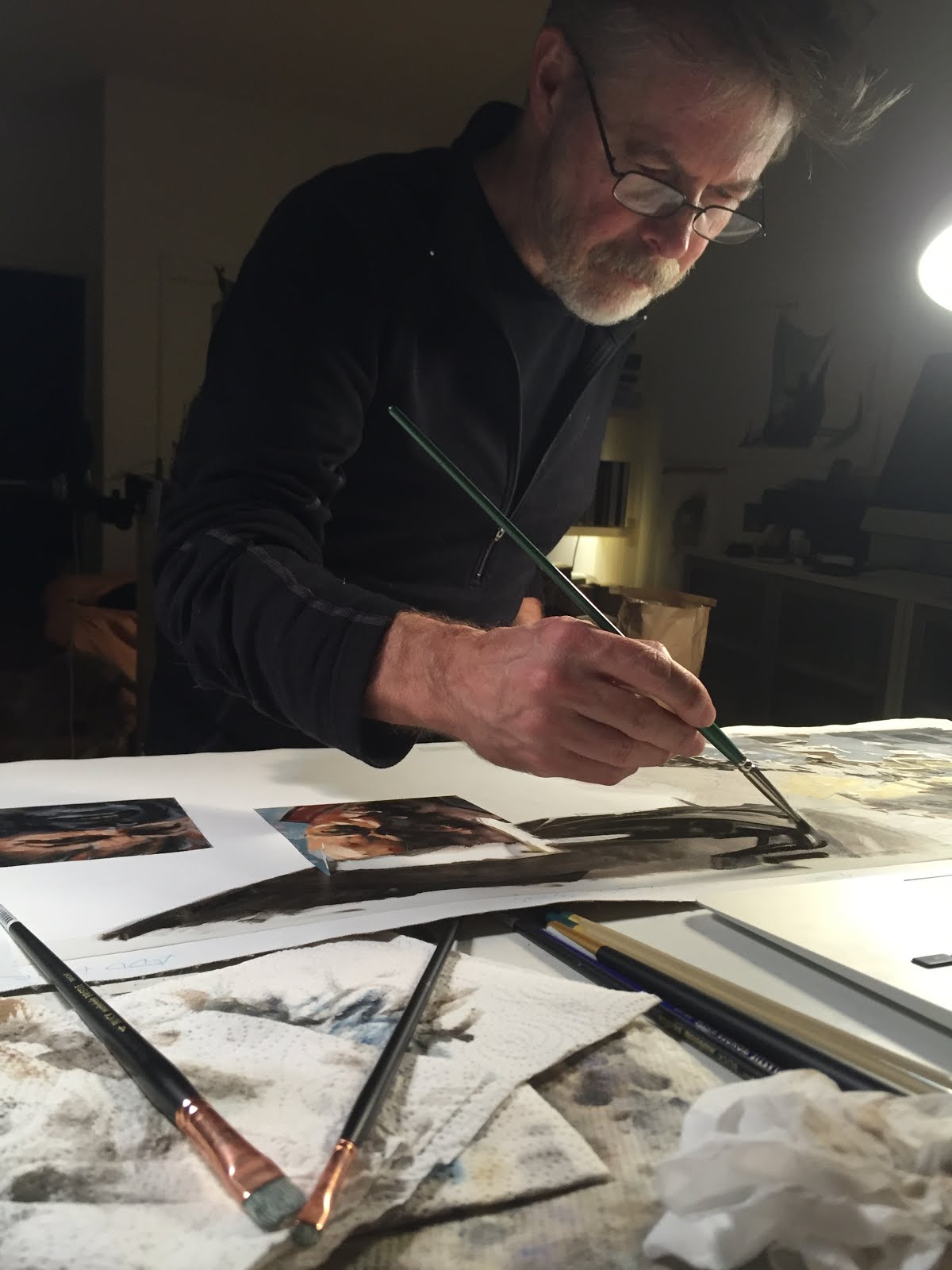

5. Painting

In a similar way to drawing, I had to allow my concerns for perfection to drift and build images with my brushwork that didn’t always tell so much detail or story in each painting. Most times I had to fight the urge to record, rather than express the image in paint. About thirty paintings in, I was able to let go of most of that worry and just allow the paint to go down. Even though I was on a deadline, it was strange to have time to set aside certain paintings to work on them piecemeal, instead of finishing each in one go. This allowed me to study them over time and make corrections and touchups.

6. Vignettes

The book started out as a panel-by-panel image book much like a graphic novel, but kept each panel vertical, in different widths across each spread. This resulted in far too many images, and would be far more work. Eventually I realized that I wanted moments of my story and not just a film on paper. My novel needed air, composition, and design. Each spread should carry the story forward or capture a moment within the tale that allows the reader to learn, reflect on, or contemplate outcome. A series of setup and reveal.

But I fell into a format that people are already familiar with and I wanted the book to be more immersive. This meant less, not more, information. I went through my thumbnail dummy book and revised each spread by composing first, and letting the viewer be absorbed by the images and therefore build interest in the prose.

Vignettes, as classic as they are, afforded the ability to not only let the reader fill in the gaps the brain loves to fill, but it also shortened my painting time considerably, enhanced the dynamic compositions, and got the image to zero-in on what was most significant.

7. Losing Focus

At seventy-five paintings in, I started to doubt. Worried about missing the deadline by weeks if not months. Had I calculated what it took to paint each spread? What would go wrong? Each painting averaged about 8 to 12 hours. Things had been smooth so far, but I had started with some simpler pieces in order to get my land legs, and now some of the more complicated pieces were still ahead of me. Some artists suggested that I should leave easy pieces for last, and others said save the ones I wanted to do the most for the final days.

I had already worked and finished paintings from different sections of the book so that it wouldn’t look as if I was improving as I got to the end. Much like the way a film is made, in separate scenes at separate times, so that there is better continuity throughout.

I figured it was inevitable that at some point I would encounter fatigue, mental and physical. The physical fatigue came in strange waves of odd rashes, and acne. Muscle pain would come and go. Mysterious aches rose up for a few days and dissipated. I worked through it instead of pampering it. For one year, I didn’t get a cold. (and as soon as I turned in the last painting to the photographer, I got a cold that put me down.)

8. Maintaining Enthusiasm

I figured I could battle the mental fatigue by resting and re-inspiring myself with new visions. Not only did I remind myself that I was alone and not having to cater my images to any client’s concerns or opinions, but I tried to keep a child-like perspective about the project that allowed me to see it from my younger self’s perspective. Would I like this if I hadn’t known the artist’s work? Would I like the image I’m working on at the moment if I saw it as a young man in art school? Did I care if anyone liked it beyond what I’d hoped?

I learned to stay involved. I kept looking at the world of illustration online, maintained a once-a-week teaching schedule, and shared images in-progress with students and professional friends.

I ended with a few easy pieces, two that I knew I could conquer, and finally the cover painting which is a re-paint of the original painting but with storyline corrections and a younger looking character.

9. Facing the Void

We all stand at the abyss in front of our canvases. The overriding factor was my brain questioning relentlessly, “what were you thinking?” “What makes you think you can do this?” “Nothing happens unless you finish this…this…thing.” And many times even harsher than that.

I think an artist has to quell these voices everyday, on nearly every occasion, to be able to accomplish anything of worth. This book was no different in that sense, but each attempt to create something like a painting is met with some form of doubt or insecurity, and one way to shield oneself from insecurity is to train and paint so much that we overwhelm the question. To understand our material so well the questions never arise.

Even the skills earned from decades of meeting deadlines and conquering assignments didn’t seem to overwhelm the things that might go wrong in creating Above the Timberline. I learned to compartmentalize those questions as often as possible, only letting them out on occasion to ask if I was on the right track to match my initial vision of the story.

But the real conflicts with any vision must be faced down with confidence in skills you’ve learned, enthusiasm that borders on the immature, and only sharing your strife with trusted individuals that know how to help you maintain your stamina. Friends.

Sharing many of those initial paintings with Muddy Colors readers provided great energy. And I thank you all for that. I hope the book brings a sense of excitement to storytelling artists, especially here, that your visions can be stirring and inspirational.

I was surprised at how I never lost interest or fascination for the story. Fatigue, fear, doubt is simply part of the process. It takes a lot.

But then, so what?

The real star here is that beard. I'll read ten things you've learned about that beard in a heartbeat.

Congrats Greg! Wow – what an accomplishment! Can't wait to see a preview. Michael will do a great job on the final book design too.

Congrats on pushing past and finishing. Can't wait to see it.

It is so encouraging to read this. I am working on my first illustrated book (of my own). Lots of similarities. Congratulations. It would be a bless to see this book.

Amazing and inspiring.

Dude. How much weight did you lose? I cannot wait for this. It's weird, every so often during the last few months I would stop whatever I was doing and wonder how Greg was doing on his paintings, especially when you would go 'radio silent' here on MC.

So when do you start on Book 2? 🙂

Having had the very good fortune of getting various in-depth previews over the last three terms of Greg's class, I can tell you that you are going to be blown away, John. It's an epic accomplishment, and the work is just stunning. This book will rock!

Ahhh just have to add to the other voices here to say, many congratulations! Reading through these updates has been really inspiring and encouraging to me (it's funny how excited I've gotten each time you make a new post about this). I'm excited to see the finished book!

SOOO excited! Have you booked any shows of the work yet? 😉

Reading the title of this post really drove home the incredible amount of work involved. Don't get me wrong, I knew you were in for quite a ride but seeing those numbers “122 Paintings in 11 Months” I seriously whispered to myself “holy sh—“.

My hat off to you Greg, you never cease to amaze, awe, inspire and motivate me to keep pushing.

Congratulations! I hope you can have a bit of vacation (or at least down time) now.

See? You guys are the BEST. Thanks so much to all for the great compliments and encouragements! It meant a LOT to me while I was painting, too.

Yeah, Sam…had to go MIA here on Muddy so I could focus completely. But I'm baaaaaack!

Scott…I'm thinking the beard has to go, so maybe I'll do a beard post. Reminds me of that poem: What's the weather in a beard? It's windy there, and rather weird…

Thanks for the fabulous early review, Dave! I will be asking everyone if they'd like to give a review of the book when the time comes. Helps with the evil Amazon algorithm…: )

Arnie…Book Two?! Wouldn't that be an awesome dream. Even though I'm ready to go for it, I'll likely be starting two other stories that I've planned for this format, plus one written by a screenwriter friend, and another collaboration on an intense historical moment in time. So much to do!

Kristina…I'm about to set up one show, and checking on another. Then there's another show in the works for the Paris gallery, Daniel Maghen, of my other paintings based on a variety of themes.

Looks like I'm about to be busy again. When do the breaks come? : )

Greg, this is incredible! Many congratulations! Like the others here, I've eagerly followed your entire adventure on MC. Loads of inspiration for the rest of us!

Now all I have to do is wait for the book to release 🙂

Daniel Maghen again?? Hooray! Any idea as to what year approximately it will happen, if it's not top-secret?

Congrats on this major accomplishment!

When will we be able to hold the product of that effort in our hands?

Well done Greg! I can't wait to see it published!

Greg, I enjoyed reading your description of what you went through to produce this amazing work. I look at your portrait of Tanya every day and am so appreciative of your talent. Looking forward to laughing with you again. Jay

Congratulations and good job! You're an inspiration, Greg, I can't wait to see your book on the shelves.

I do hope you give your body some time to recover. But on the other hand, wow. Keep blazin' ahead, man. (Three more stories in the pipeline?! SWEET!)

Very inspiring. I won't ever work as an artist, being a very happy Occupational Therapist, but I'm working on drawing and painting better. I tend to use 'lack of time' as an excuse, but if you can do that many canvases in 11 monhs and fulfill other commitments, then I think I can make a couple of sketches a day.

Right then…

Pretty much can not express how excited I am for this book!

Thanks for sharing your process (journey). Congrats on the project and can't wait to see it!

Look at the pile of linen!….I'm surprised the floor doesn't fall through. What did you do, buy out the factory:)

Can't wait for the book, but really looking forward one day to hopefully see the real ones in person.

Very Cool Greg, see I told you you were a good painter! 🙂

Cannot wait to see it all laid out.

(Oh, and Scotty is right. Is the beard symbiotic?)

Amazing work Greg! Congratulations.

You're a real inspiration, Greg. Congrats and thanks for the ongoing inside views on the work and the process. Maybe you could speak a bit about how you used feedback here and elsewhere?

(I worry about your neck, hope you know your ergonomics!)

This was a great and very insightful read, Greg. Thank you for sharing so much of your process, insecurity, and dauntlessness. What I think I found most heartening in your words was that, despite all of your extensive professional experience, you still had to face doubts, and even had to account for your own improvement, shuffling your focus on which piece to do when, so that it all has a smooth flow. Kudos, and I hope your book is a success!

Amazing! Congratulations on getting to the finish line. Thank you for letting us take a look at the process and sharing your thoughts about taking on such a massive project. I can't wait too see the book, and also i hope there will be some way to look at the original paintings in some way. Are you planning to have a show with them at some point?

So inspiring! The very idea of committing to that many paintings in a year is staggering. I look forward to the book!

Truly amazing!! It was so exciting to see your work come to life and can't wait to hold a copy in my hands. My husband looked over my shoulder once and his face lit up with boy adventurer's joy! Thanks for sharing your journey and challenges.

Excellent post, Greg! It was a real pleasure getting to see these images in class as you were creating them. Can't wait for the book!

Did you start them as grisailles as some of the shots suggest?

Very, VERY inspiring, and I think most of all, there's major impressive WISDOM in this article! Your thoughts are as well crafted and honed as your considerable artistic skills and vision. Thanks for sharing so generously and honestly about the trials of creating; this is an article I will return to many times for the kind support and insights it provides to an illustrator on their path.

You're an inspiration, Greg! Thanks for letting us share this awesome moment with you. I can't wait to see the finished product, and I'd be glad to give a glowing review on amazon once I buy it and get it in my hungry hands!

Wow….you cannot know how fun it is to read so much good will here. THANKS EVERYONE!

Now I'll try to answer a few of the questions…But first, big SHOUT OUT to JARED SHEAR who supplied me with canvas at a moment's notice! THANKS, man! If y'all need low cost art supplies, contact this guy! And he's a helluva painter, too!

I doubt there will be a show at Daniel Maghen this coming year, but hey…I could handle one now, right? : ) But I'm certainly hoping for 2018. Keep checking as John Harris has a show coming up there, too. LOVE his work.

Sebastian: release date is planned for Autumn 2017!

Jay! So nice to hear from you here! That portrait of Tanya was a breakthrough piece for me.

Andy: enjoy! You can do it. It's mostly process.

Mike: the beard was inspired by Mike Mignola. But it may be coming off soon!

Mark M: I used the feedback to keep my brain on target knowing that there are others out there that appreciate similar things as I do. It's all we have. To try to do a project that is attempting to capture a large audience is rarely successful as it tries desperately to please too many at once. Focus on what appeals to you and you'll find an audience that's much more solid.

Brandon: I'm certain there are artists that never feel the challenge, but then, do they really? Although I love it when I see a painter go after something and it feels like they just had to do it no matter what, no matter the consequences. Almost fearless.

Adam: hoping to have a couple shows of the originals. You'll certainly know when and where!

cr: 'boy adventurer's joy'….THAT'S IT! So happy to hear that….

Colin: more coming up in class!

Mark M: no grisailles…just middle tones, then darks, then build to the lights….

glenda: so glad to hear that, g! I do hope it helps over and over again…

Kyle, et al: thanks again for the great comments! I want the book to inspire you ALL to tell and paint your own stories. Let's get these publishes begging for more!

G

I meant publishers. (Stupid spell-correct)

Nooooo! I love the beard! Big big congrats on finishing up Greg. I know it was an enormous project – but it looks amazing. Can't wait to see it all together.

Congratulations on your grand accomplishment. Inspired and awestruck by your talent and creative process. Long journey from the studio in Galena. Bill Brauckman

You did it! Amazing, Greg, nicely done. Inspiring!! And since I lurked in your class a while back, I am now underway on my own insane art story project. See what you started?? Can't wait to get the book!!

Bill! Thanks! Wow….been a long time! Hope you've been well! Kirk and we should catch up through email or something. manchess@mac.com

Deunan! Mu-hahahahaha! You have fallen into my evil plan for all illustrators! I will be writing more about the process surrounding the book. I wish you all the best, and any suggestions or help for your vision!

Enjoyed this, honest and encouraging for the endeavors ahead, looking forward to 'Above the Timberline'.

Cannot WAIT to see this Greg!!! Been following for a while now and through Mark B. Congratulations! 🙂 e

Congrats on such an absolutely amazing accomplishment! I'm looking forward to checking the book out and adding it to my library.

Greg, you did an amazing job of creating an audience around this project! It's so fun to follow along and feel personally invested. I'm not much of a reader or book collector, but this is “on my list.” 🙂

-David

If there is a book to do out there that needs 11 paintings in 122 months I'm your man. I can't tell you how inspiring this is Greg.

I hope there will also be a book about the making of the book, maybe a book titled… “Things I Learned From Creating 122 Paintings in 11 Months” 😀

Seriously though, if you have more wip pictures like those, I'm sure a lot of people would want to buy that book.

“There's one guy on the planet that can do that and it's me.” Greg Manchess

Quoted from an IMC talk. I can't wait to get my hands on this book. Thank you so much for sharing all this Greg.

Muito bom, muito bom!…

Muito bom, muito bom!…

There are myths that pervade of people that are born with gifts, and no matter how hard we may try- we will never equate these blessed types.

This is normally called talent.

Reading this article- I would dare say that talent is only the beginning. Of course, being able to draw and paint helps.

But it is only one part to the story. Work is nutrition for the soul.

Watching this evolving process in this article take shape over time, I assure you that hard work and perservernce overcame talent any day!

The sheer effort and no quit attitude required to make this book happen trumps any preconcieved notions of talent.

I look forward to owning a copy, and if I'm lucky enough, one day I may get an autograph.

Bravo sir!

This looks so amazing, daunting and fun.