Paul Cadmus was an American painter who was born in Manhattan, New York City in December of 1904 and died in Weston, Connecticut in 1999. His work, mostly drawings and paintings done using egg tempera, has been categorized as magic, or social realism by some art critics and scholars, which consisted of nude or semi-nude male portraits and satirical scenes of American life. Cadmus worked as a commercial artist at a Manhattan advertising agency called Blackman Company where he made illustrations and did layouts. In 1931, less than two years after he was hired, Cadmus quit his job and traveled to Europe with his lover, the artist, Jared French where they lived for another two years until their money ran out.

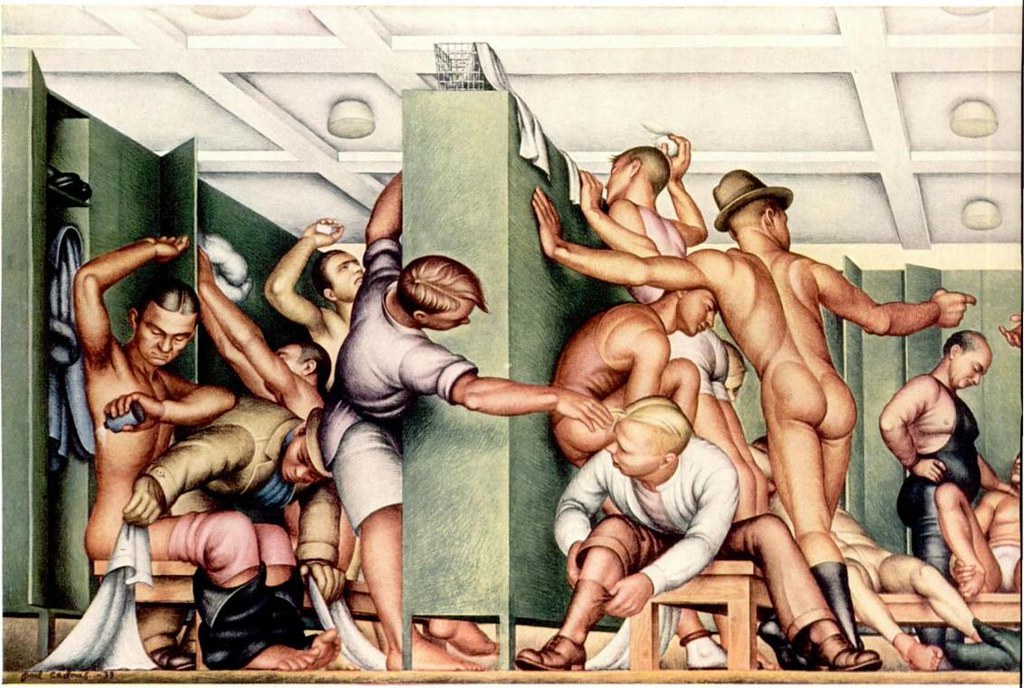

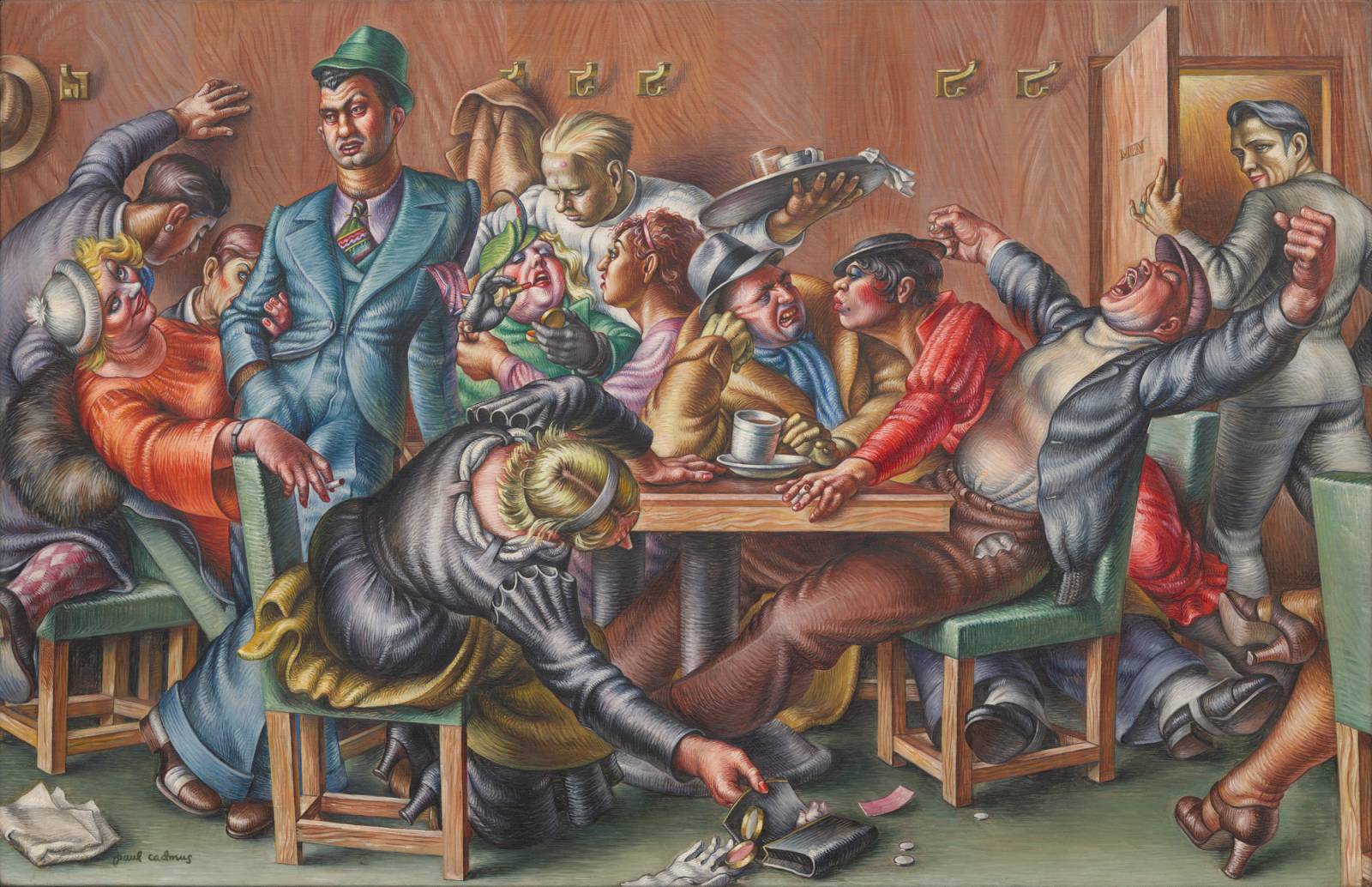

Shortly after their return to America, Cadmus was hired by the Public Works of Arts Project (PWAC) in 1934 to create two pieces of art, The Fleets In! and Greenwich Village Cafeteria. The former shows the daily lives of sailors on shore leave, but in various stages of drunkenness and debauchery. This painting was selected to appear at an exhibition of PWAP at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C.; however, when the exhibition opened, the Navy’s Admiral Hugh Rodman ordered that it be removed because he felt offended by the ways in which the sailors had been depicted in it. Whether intentional or not, Cadmus, who was gay, codified gay male desire and identity through his subject matter. Referring to this painting alongside another one of his, Finistère, helps to better explain the way in which Cadmus’ work was influenced by his homophobic social surroundings that coincided with the rise of capitalism, both of which helped to incite the formation of gay identity in America during the early twentieth century.

In Finistère, the man in the front center of the painting is straddled on his bicycle looking towards his left side. His skin is unusually white with tones of blue and pink, and his hair is a blond pompadour. His back faces us, and he is wearing a long sleeved, pale blue shirt, and a similarly toned blue bathing suit. The front end of the bicycle seat rests in between the rounded cheeks of his buttocks, pushing the bathing suit fabric into it. The angles of his thighs diagonally cross the seat and crossbar to create a locus of (homo)eroticism. He stares at the man on his left, who is equally scantily dressed. His skin is darker, perhaps because he is a local. Referring to the title of the painting, and the fact that Cadmus lived in Europe for two years with his lover, Jared French, we can assume these men are near the coast in the French region of Finistère. The man on the left stares blankly off to the side however, the fact that he is leaning towards the man on the bicycle and is partially revealing the top of his pelvis suggests he is flirting. At the same time, we see the man on the bicycle holding a baguette which rests along the handlebar, which probably represents his erection. In the background there is a young woman wearing a bikini who is drawing or writing, and nearby is what appears to be a fisherman. His pose seems too relaxed — almost flirtatious, the way in which he is thrusting his hips to the side. But he is not looking at the woman, instead his head is slightly turned towards the two men who are cruising each other.

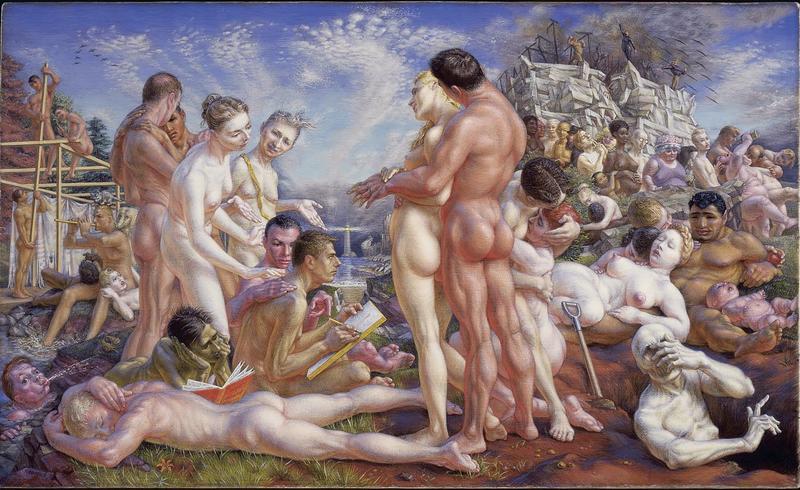

As in many of Cadmus’ drawings and paintings, he celebrates the male physique, highlighting their bulging muscles and homing in on their pelvis and groin. Although Cadmus admitted that he did not purposely depict homosexuality in his pictures, rather he was satirically capturing American life, he was the first artist to portray male homoeroticism in them. Particularly the “fairy,” a denigrative term which was also compared to the “floosy,” a term used to describe a promiscuous woman, gay male desire during the 1930s was placed alongside female characteristics and wants. His inclusion of gay men in his paintings was the first time that homosexuality appeared in American art according to Richard Meyer in his book, Outlaw Representation “because of a complex interplay of social and artistic factors.”[1]

Homosexuality during the 1930’s in America was still in an oppressive stage resulting in the “formation and increased visibility of gay male subcultures.”[2] Speak easies sprang up and Cadmus, along with some of his friends, held cocktail parties which allowed his guests to live outside of the closet for one evening. These were gatherings of “art-world beauties, where youthful naiveté met social suavity, contacts were made and careers launched.” [3] Because of the oppressive conditions of the time, Cadmus’ friends who were also gay, were married to women. Lincoln Kirstein, who was the co-founder of the New York City Ballet, was married to Fidelma, Cadmus’ sister, and Cadmus’ lover, Jared French, was married to the artist Margaret French. These gatherings became a cultural bookend for queer art in America, marking the beginning of it.

In eighteenth century colonial New England, families functioned as a cooperative inter-dependent unit. The household was led by the husband, and he, his wife and children farmed the land; sex during that time was aligned with procreation and labor, “the birthrate averaged over seven children per woman of childbearing age. Men and women needed the labor of children.”[4]

Emergence of the bourgeois society in the nineteenth century gave rise to merchants and entrepreneurs, which allowed for more independence. The production of goods and trading gave rise to a wage economy in which individuals were no longer forced to rely on each other for survival. Households moved from a feudal society towards capitalism. This meant that family members no longer had to work alongside each other, and that men and women could seek out work and earn money outside of the home.

The free labour economy was in full swing into the early to mid-twentieth century. Concurrent to the new economic freedom that was being experienced by many individuals was also a new sexual freedom. As men and women were no longer confined to keep a heteronormative familial model intact for survival, a kind of sexual revolution came into existence that was amplified by the war, “capitalism […] led to the separation of sexuality from procreation.” [5]

In John D’Emilio’s essay, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” he proposes that young men and women moved out of their heterosexual homes into same-sex barracks because of the war, and thus new queer spaces were created.

“The war freed millions of men and women from the settings where heterosexuality was normally imposed. For men and women already gay, it provided an opportunity to meet people like themselves. Others could become gay because of the temporary freedom to explore sexuality that the war provided.”[6]

This also meant that when these men and women came back from the war, or were on shore leave, that they were more visible than before and more inclined to seek out one another. Particularly gay white men during this time had more freedom to express their homosexual desires publicly because of their financial independence, “capitalism has drawn far more men than women into the labor force, and at higher wages”[7] as well as their gender, which was linked to power (it was safer for a man to be alone in public than a woman, “streets, parks, and bars, especially at night were “male space.”)[8] In Finistère and several of Cadmus’ other works we see these erotic situations unfolding in plain sight.

Before capitalism, homosexuality was considered only as an act, or behavior. But as gays and lesbians became more visible, and began to function more independently from heteronormative society, they started to form new queer identities which provoked homophobic governments to oppress them. Cadmus’ paintings became part of this conversation whether intentional, or not because he captured figuratively, and with great detail, the behaviour of the gay men he observed and with whom he socialized, and then with a subverted swish of his brush, freed them by painting these men into American art.

* Thank you to Li An for correcting some errors in this essay in regards to the details of some of the subject matter within Cadmus’ piece, Finistère.

[1] Richard Meyer, Outlaw Representation: Censorship & Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (Beacon Press, 2002), 26.

[2] Ibid., 27.

[3] Jennifer Greenhill, “Review of "Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein, and Their Circle" by David Leddick. Archives of American Art Journal, 1999.,” accessed September 27, 2019,

[4] John D’Emilio, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” in Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, ed. Ann Snitow, Christine Stansell, & Sharan Thompson, New Feminist Library Series (New York, 1983), 104.

[5] Ibid., 110.

[6] John D’Emilio, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” in Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, ed. Ann Snitow, Christine Stansell, & Sharan Thompson, New Feminist Library Series (New York, 1983), 107.

[7] Ibid., 106

[8] Ibid., 106

Bibliography

“1934: The Art of the New Deal.” Smithsonian. Accessed October 6, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/1934-the-art-of-the-new-deal-132242698/.

“American Regionalism Movement Overview.” The Art Story. Accessed September 27, 2019. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/american-regionalism/.

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. 4/19/95 edition. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1995.

Greenhill, Jennifer. “Review of "Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein, and Their Circle" by David Leddick. Archives of American Art Journal, 1999.” Accessed September 27, 2019. https://www.academia.edu/10004588/Review_of_Intimate_Companions_A_Triography_of_George_Platt_Lynes_Paul_Cadmus_Lincoln_Kirstein_and_Their_Circle_by_David_Leddick._Archives_of_American_Art_Journal_1999.

“LGBTQ Activism: The Henry Gerber House, Chicago, IL (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed October 6, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/articles/lgbtq-activism-henry-gerber-house-chicago-il.htm.

Meyer, Richard. Outlaw Representation: Censorship & Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art. Beacon Press, 2002.

John D’Emilio, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” in Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, ed. Ann Snitow, Christine Stansell, & Sharan Thompson, New Feminist Library Series (New York, 1983).

Interesting post. As sexuality is something quite absent in the themes showed on this blog, it’s interesting to have a view on a artist who’s sexuality emerges in his pictures. I’m quite surprised you did not mention JCLeyendecker, a gay artist very popular (not as gay :-)) as his males representation seems very gay for today audience.

Two little errors : Finistère is not a city but a French region (see Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finist%C3%A8re). And it’s not a police officer but a fisherman with his very classic blue cap.

Cadmus would have paint a “gendarme” and gendarmes were always in pair when patrolling.

hi Li-An, thank you so much for posting!… i’ll make the corrections – grateful for your comments 🙂 … yes, Leyendecker came up as well in my research, but due to a lack of time, i wasn’t able to insert information about him, or go more into depth about Cadmus — George Tooker is another one, as well as his art trio PaJaMa with Jared and Margaret French and their time spent in Fire Island, NY (which i go to every summer) …Writing this essay felt like i was meeting so many ghosts…. in any case, i’m still working this… would love to post the final essay in a few weeks .

Great article, Marcos! It’s always fascinating to peek behind the curtain at the cultural and political and economic forces at play behind an artist, and doubly so for how our identities and lived experiences come out in the art we make.

thanks so much Lauren… i enjoyed writing it… and will continue.. there’s a bunch of other research material that i wasn’t able to insert because of time, but Cadmus is one of my faves so it’ll be worth it!

Fantastic post! I can’t believe the dates on some of those images. 1933?! Talk about brave!

yeah man! he painted some of them while he was living in Majorca ! i think The YMCA locker was painted while he was living overseas