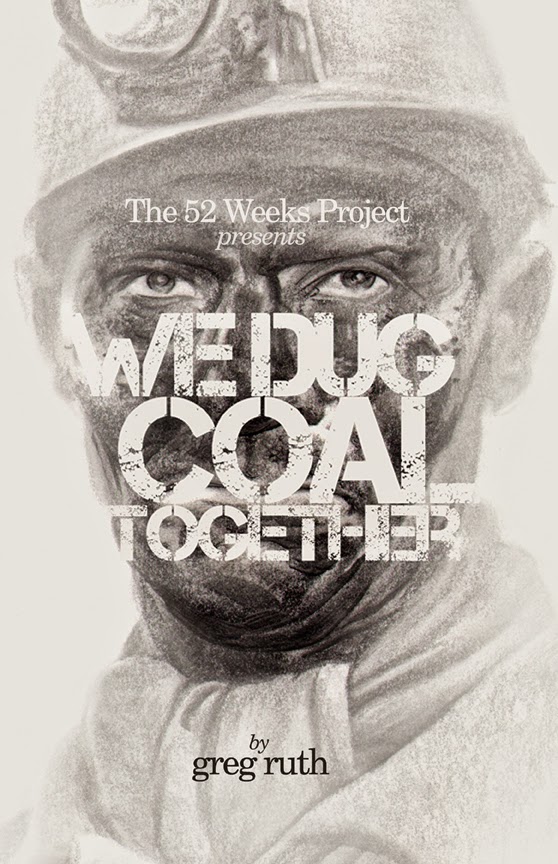

When you make art for a living, the act of making art can and does become at times, drudgery. I found myself waking up Monday mornings groaning as anyone would going to work, (ridiculous as that sounds). One of the most diabolical side effects of achieving the rare feat of working as a professional artist, will inevitably have to contend with wrestling with the encroaching ground of work and money and other compromises that will encroach into your once verdant and isolated landscape. It’s just going to happen and I have found instead of trying to fight off the hurricane, it’s better and more effective to learn to surf it. One of my favorite means by which I do this surfing is The 52 Weeks Project- which is basically publicly committing to making a new drawing each and every monday. Sort of the art equivalent of eating dessert before the meal.

As is per usual of the very broad scope that is the cornucopia of The 52 Weeks Project, this is anti-assignment, anti-work. It’s the one protected sandbox of pure play, and as I have become more and more familiar with my new graphite drawings, I thought it a perfect time to really push them to see what they can do, and what they cannot. Typically these weekly drawings have been executed in sumi ink- which makes perfect sense. It’s quick free and gestural. Getting the graphite to not gobble the whole day up (there’s a point when one does actually have to get back to work), has been tricky to try and discover. this series is an attempt to do so.

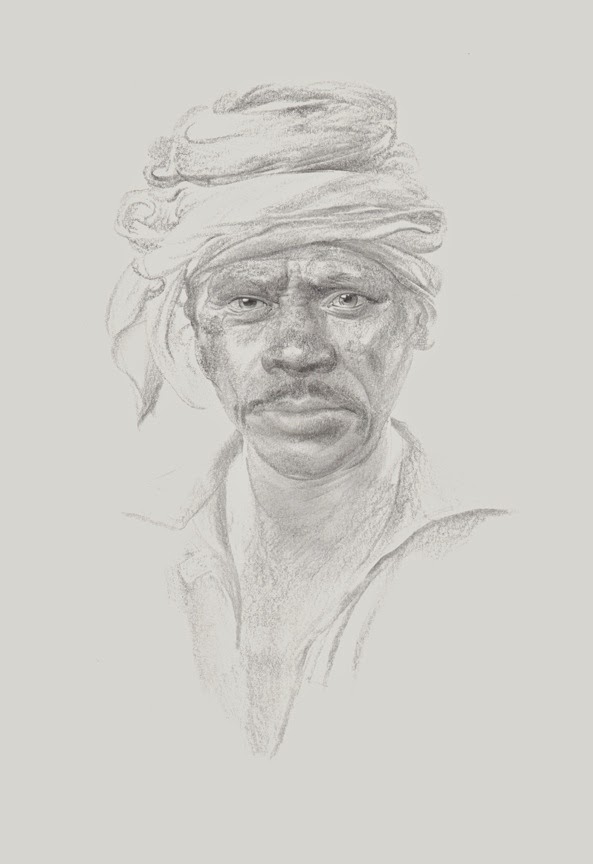

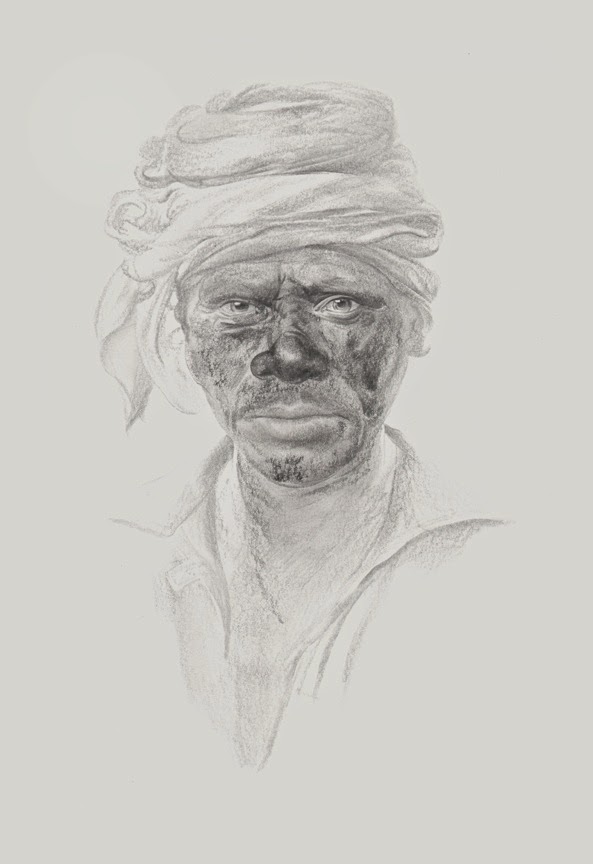

As always I am a HUGE fan of portraiture. There’s something about the task reduced to a human face that is forever compelling and captivating to me as a drafstman. It’s a drawing that looks back at you, and so much of where the character lies, is in not just the usual areas of eyes and mouth, but everywhere throughout the face, the garb, the way the subject holds his or herself… I’ve had an ongoing fascination with old coal miner photos, and especially the through line they all share. That same sooty face, that same determined focus in their eyes. Throughout the whole of photo-documented miners, they all seem, no matter what country they’re from, to possess a common gaze, look and feel. They are of a people together and represent the frontline of our relationship with this heating/energy/fuel source of ours since the ancient Greeks first began to record its effect and its potential. Coal has shaped our world, driven our societies, and stood invisibly behind nearly every major epoch in human history from the advent of the iron age, through the locomotive and today’s sophisticated electrical grid. it as a rock made from decomposition, and its exploitation has given rise to empires and now threatens to alter the very environmental structure of our planet. From Asia to Europe, to our Americas and over to India, Africa and the Middle East, Coal has dominated and permeated itself into nearly every human society on earth. Rich and fertile ground for exploring it in an apolitical anthropological way, and I can think of now better locus point around which to learn more than through the faces and hands of those who burrow deep and pluck it from the heart of the earth.

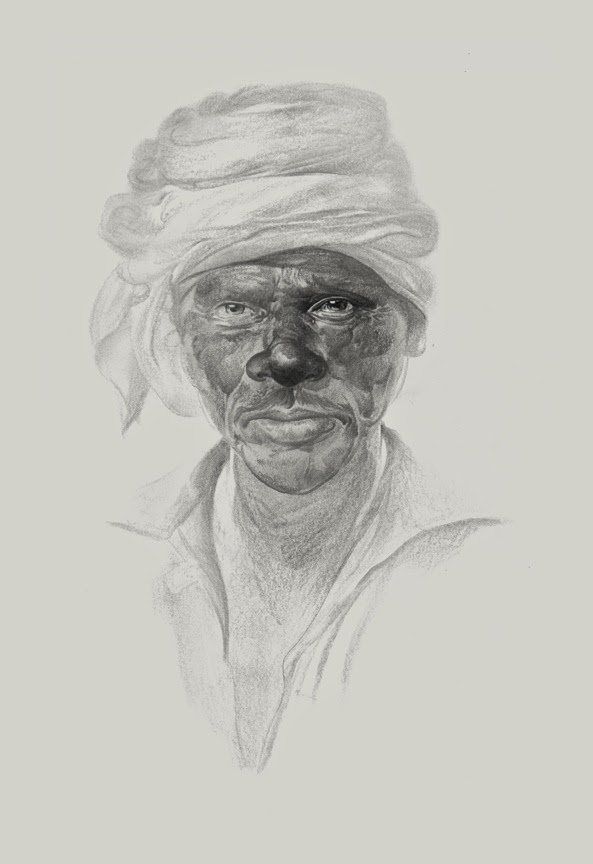

So here’s the tools of the trade. I tend to begin with the lightest underdrawing using the Staedtler all-graphiter HB, and then progress towards the final Blackwing Palomino for the darkest and most detailed bits. Basically erasing and smudging maniacally with my thumb along the way.

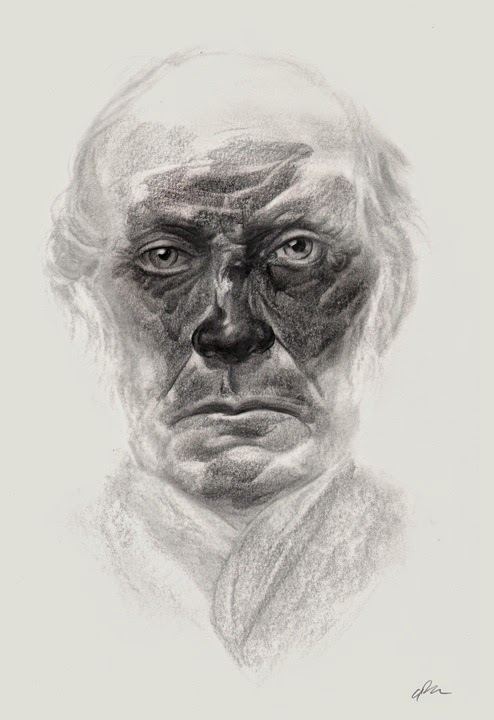

Here’s the very first portrait, which when it was done grabbed me by the top of my head and utterly against my will dragged me into this project. I had intended instead to spend a few weeks exploring the images of Weeping Maidens, but instead this fellow came in and overturned the tables. It took around an hour to execute- more than twice as long as a typical 52 Weeks style image- but there was simply something undeniable about him, and about the potential of this series.

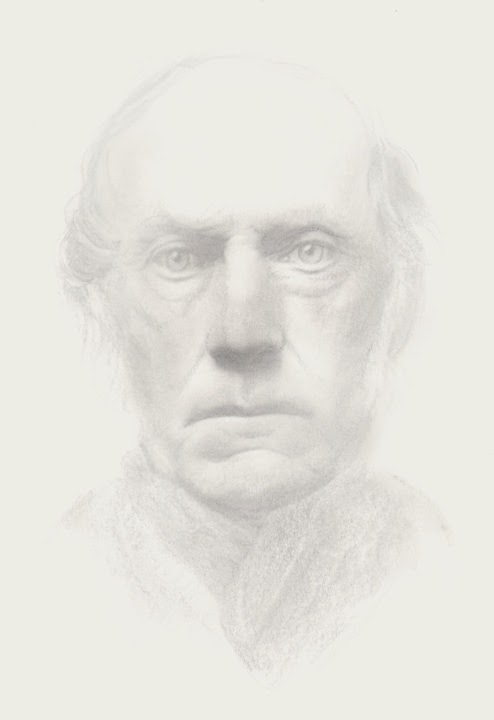

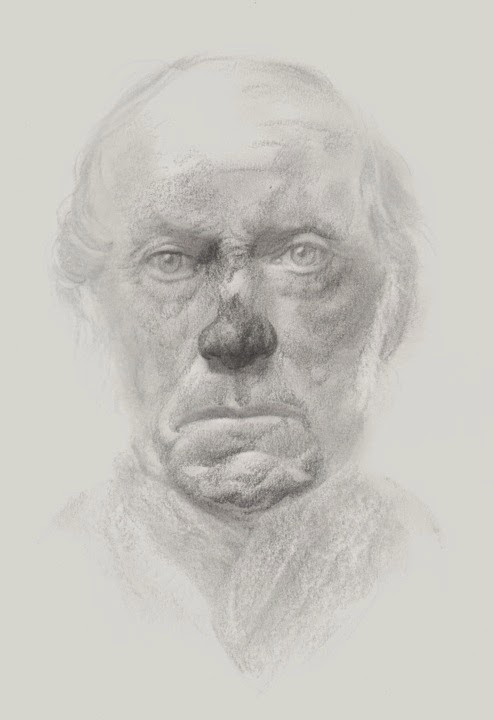

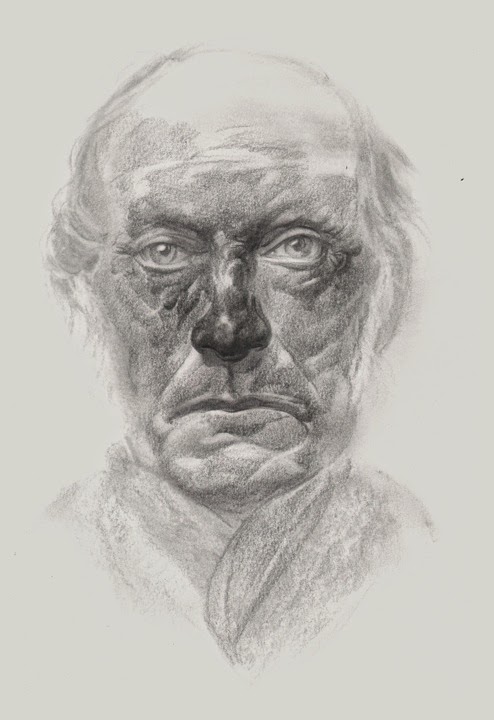

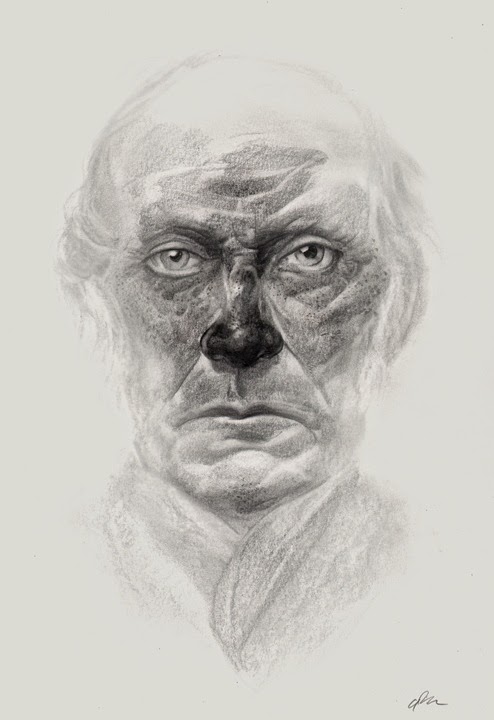

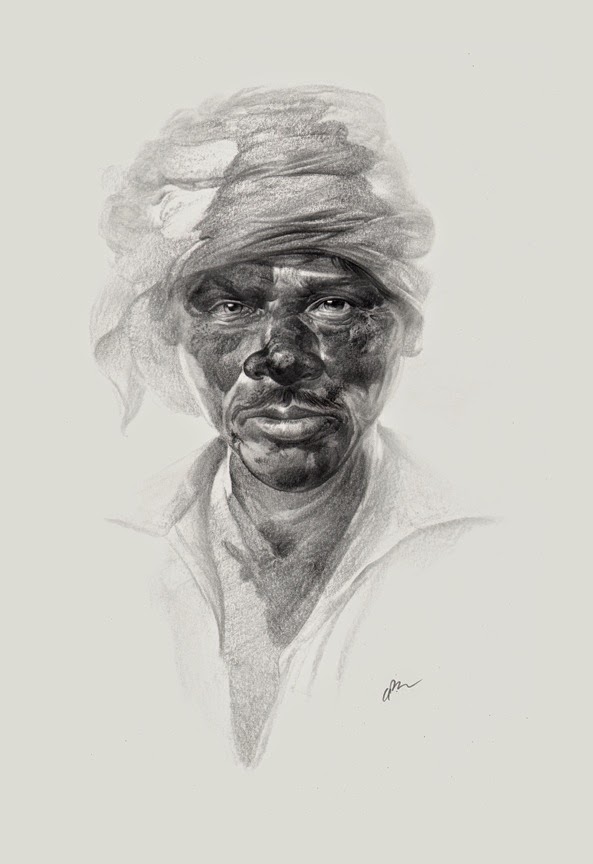

For the second piece, I decided to go back a bit and focus on the 1800’s area and England specifically. In a given coal family it was entirely typical to find every male generation working the mines alongside each other. The process of going in and coming out after a day inside the sleeve seemed to beg trying to do something a little different this time. Instead of going in with a full on attended coal-face I wanted to draw the piece clean at first and apply the soot as part of the finishing of the drawing. The technical aspects aside the thing that struck me the most was how it ages this fellow.

As an artist, it’s a chance to explore the idea of a face, the smudges and smears that both hide and mask it but also define and carve it into what it is. It is the leftover of interacting with it. Dark and filthy and sooty as a moonless night. A perfect arena to take the graphite pencils out for a good and long term spin.

Great concept, riveting portraits. The eyes are amazing. Thanks for sharing Greg!

Greg-

These are really good. I like how you just focus on certain area's and leave the rest in a haze. Have you ever tried using Q-Tips to blend your pencil work? I fell in love with those a long time ago. Thanks for sharing-

Thank you- yes it is all about the eyes in these. Make or break happens there, so I tend to start and focus on getting that right- if not, crumple it and do another. There is no portrait that delivers if the piece doesn't look back at you in some way.

That's a good idea- never tried it out- always just use my finger! Qtips will be tried out later today. Love the MacGuyver school of artmaking.

You might try using a good sable or soft hair brush for blending, that will allow better control of how much to blend and the area being blended.

I'm trying to get into doing larger-scale graphite drawings at the moment, it was a treat to see this article pop up. Very inspiring drawings, both in the craftsmanship and content. Thanks for sharing this, Greg.

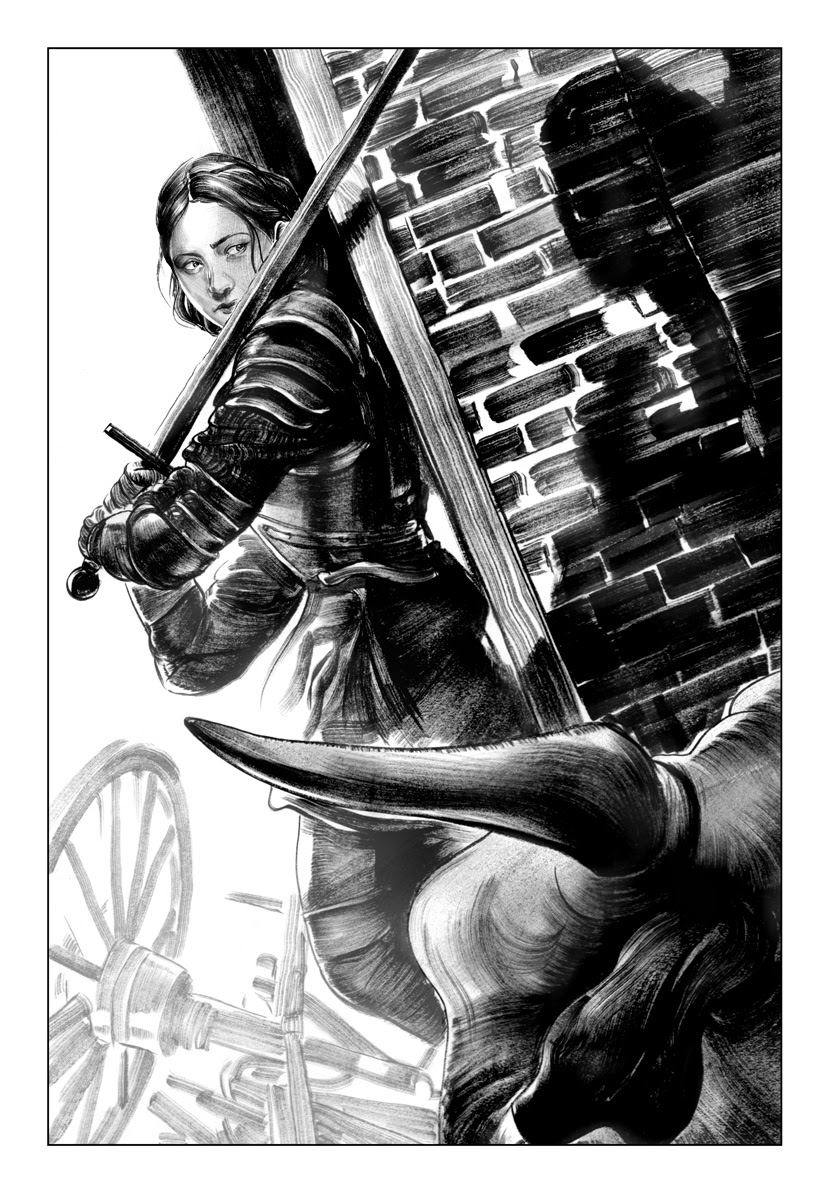

Beautiful cover ! This type matches perfectly with your portrait, both in style and content, well done.

What sort of paper are you using?

I'm working on a large big hed in aohite right now. Totally different animal isn't it? These are fairly nirmal sized- 9×12 at biggest, some smaller. Find the gigantic variety carries it's own benefits though.

Thanks, Pierre!

I alternate between my standard bookweight Strathmore Alexis drawing paper and this 350 gsm cotton rag stuff which has a nice tooth to it.

Absolutely beautiful, great breakdown of process as well.

Thanks! I intend to bring a couple of these in their early stages to complete on site at IMC in a couple weeks.

One of my favourite aspects of art is the way it can make you think about things you might not have even considered before… So thankyou for such a compelling insight into coal mining! And of course, it goes without saying that your portraits are gorgeous. I adore the way you control detail and contrast!