The illustrated novel has held a special place in my heart ever since I first visited the Brandywine Museum and saw N.C. Wyeth’s Treasure Island paintings. Standing in the gallery and seeing the story all laid out hooked me completely. There was a rhythm to the presentation. The drama played out in chapters, and there was unity but it was never redundant. Like looking at a map and imagining the stories that might take place there (which, incidentally, is kind of how Robert Louis Stevenson actually conceived of Treasure Island), each image was a reveal and cliffhanger all in one. Each moment was important. The space between the moments activated my imagination.

So it only makes sense that I would jump at the chance to work on projects like this. Though they had fallen out of fashion for many decades, there are a few publishing houses that specialize in illustrated editions and I’ve been fortunate to be involved with about half a dozen to date. My most recent of these was to create 16 interiors for a special reprinting of Nightflyers by George R.R. Martin releasing this week from Bantam Books. I thought I’d talk about some lessons learned from working on these projects.

Get Ready For A Marathon

The first challenge you’re confronted with in this type of commission is the scale and scope of it. In my experience, these jobs most often seem to be in the 8-12 finished pieces range. While that may sound no different than just having 8-12 normal commissions lined up, there are certain bottle necks and obstacles that I’ve found. Not least of them, some basic psychological hurdles in maintaining consistency over the whole run.

When I’m bouncing from client to client, I can constantly rearrange my priorities as needed: pushing something back when a short turn around jumps up, working on job B while job A get’s their feedback sorted, and pacing things out so that I can sketch on one job, finish on another, and work out contracts on a third all at the same time. There is a dance to the freelance calendar. A fluid forward motion that rewards efficiency and rotates tasks to prevent fatigue.

Illustrated books don’t have that flow to them. If normal jobs are a relatively steady stream, this type of project is a huge chunk ready to block the pipe. It needs to be broken into smaller pieces and worked into the flow gradually, otherwise there’s going to be problems.

Pacing The Story

Unlike one-off assignments, a set of interiors are meant to be seen together, so I’m strongly of the opinion that they should be planned together. It might be easy to just stagger the individual pieces over the time allotted and work them one by one, but that won’t allow for the big picture planning that makes a contained series of this type successful. The work should be unified. The designs consistent. The compositions, the choice of scenes, the colors and themes… The total body will, in the end, represent a complete expression. In that way, it’s almost like designing a portfolio. A coherent voice with variety. Each piece adds to the big idea without being repetitive. Planning as a group also allows more consistency and efficiency in casting models for your characters and maintaining continuity for repeating props and wardrobe.

For this reason, I find it best to finish ALL sketches before I start on finals. That leaves the flexibility to revise and adjust when unexpected problems or new ideas pop up. And it let’s you see the whole sequence together before you’ve committed to anything.

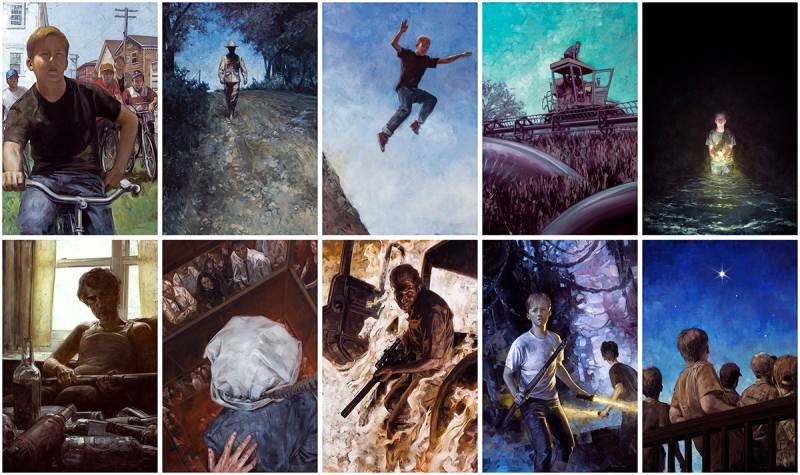

The final batch of sketches for Nightflyers as presented to the publisher. In some cases, I only presented one idea when I felt it was clearly the best take for that beat in the context of the full sequence

Step one is choosing scenes and you immediately understand why planning as a group is important. If all of the most interesting visual moments happen in just one or two chapters, that’s not going to work if they need to be spread throughout the book. And it does not represent the full experience of the story. I prefer to break it all into blocks. If there are 10 interiors needed, I’ll bookmark out ten equal segments and look for the most key moments in each one. If needed, I might then wiggle a bit, but this gives a good starting point. You might find with this method that the most interesting moment in a section is a very quiet beat, or simply a portrait. The beauty of this type of project is actually having time for those images. They are important in the larger picture and are honest to the tone of the story.

Pacing The Money

This one is really important. While it’s nice to be working towards that big payday, projects like this take months to finish. And however you structure that, I’ve found that keeping the money steady is ideal. It also will help keep the work on task, hopefully. The reality is that we don’t get paid from working, we get paid from invoicing. If you are setting aside time from the normal flow of invoices to work on this long range job but are not getting paid installments along the way, you’ll notice that you’re not making enough each month because Big Project time isn’t getting billed. I have found breaking up into milestones (for example: signing contract, sketch delivery, 1st half or finals, 2nd half of finals) or simply monthly installments work best to avoid income gullies.

The interior pieces from Salem’s Lot by Stephen King (much more detail about that project here)

Pacing The Work

The flip of this is that you NEED to plot and follow a schedule to get the work done smoothly. If short term deadlines keep pushing things back, you’ll find one day that you don’t have enough time to do the job properly. There are two really bad things that happen if you let it all sit until the very end. The first and most obvious is that the finished work is rushed and not up to standards. The second and less obvious is that now you have to turn down any new jobs just to get the book done on time. If you’re being selective about new work along the way, you can say no to the small fish and yes to the sweet opportunities. If, on the other hand, you find yourself squeezing four months of work into 60 days, you can’t say yes to anything without making matters even worse.

And if you negotiated a staggered payment schedule but left all the work to the end, you kind of deserve to experience the dread of realizing that you will have no invoices going out while you scramble to finish the project that you’ve already been mostly paid for. I recommend not doing that.

What Really Matters

The real trick, in the end, in a solid run of paintings. And this has been my hardest lesson learned through experience. If you run short of time or half bake a scene concept and it results in some weak pieces in the mix, that’s going water down the whole group. A really successful set of images, again like a portfolio, needs to stand as each individual as well as together. And I think hitting that consistency is the real challenge, and the real evidence of a disciplined approach. Luckily, you should have a lot of time to work out those kinks. A lot of opportunities to correct your attitude if you’re feeling lazy. Because it’s a marathon, and that means preparing, taking the scale of the task seriously, and pacing yourself.

Thanks David, great article – and the work looks amazing. Some real good advice in there about long term planning, very helpful!

Thank you for this. Do you have any more thoughts on how you decide what moment to illustrate?

Whoa, you did an illustrated version of Summer of Night?! One of my favorite books illustrated by one of my favorite artists? Damn.

Wow your work is incredible. Your Summer of Night and ‘Salem’s Lot scenes are exactly how I pictured them.