On a recent trip to London I had the good fortune of being able to spend some time in the Tate Gallery. There are many masterpieces in this wonderful and accessible museum. One of the standout paintings for me, is Ophelia, by John Everett Millais.

Here is a giant scan of the image found on the Google Art Project site.

I love this beautiful pencil study of the model, Elizabeth Siddal.

The work was painted, of course, after the character and scene from Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet:

There, on the pendent boughs her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious sliver broke;

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up;

Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes,

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element; but long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pull’d the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.

According to the Tate website, Millais painted the background first, carefully observing nature and recording all the detail he possibly could. It sounds like it was an arduous task!

My martyrdom is more trying than any I have hitherto experienced. The flies of Surrey are more muscular, and have a still greater propensity for probing human flesh … I am threatened with a notice to appear before a magistrate for trespassing in a field and destroying the hay … am also in danger of being blown by the wind into the water, and becoming intimate with the feelings of Ophelia when that Lady sank to muddy death, together with the (less likely) total disappearance, through the voracity of the flies … Certainly the painting of a picture under such circumstances would be a greater punishment to a murderer than hanging.

(J.G. Millais I, pp.119–20)

More from the Tate website:

The model, Elizabeth Siddal, a favourite of the Pre-Raphaelites who later married Rossetti, was required to pose over a four month period in a bath full of water kept warm by lamps underneath. The lamps went out on one occasion, causing her to catch a severe cold. Her father threatened the artist with legal action until he agreed to pay the doctor’s bills.

The plants, most of which have symbolic significance, were depicted with painstaking botanical detail. The roses near Ophelia’s cheek and dress, and the field rose on the bank, may allude to her brother Laertes calling her ‘rose of May’. The willow, nettle and daisy are associated with forsaken love, pain, and innocence. Pansies refer to love in vain. Violets, which Ophelia wears in a chain around her neck, stand for faithfulness, chastity or death of the young, any of which meanings could apply here. The poppy signifies death. Forget-me-nots float in the water. Millais wrote to Thomas Combe in March 1852: ‘Today I have purchased a really splendid lady’s ancient dress – all flowered over in silver embroidery – and I am going to paint it for “Ophelia”. You may imagine it is something rather good when I tell you it cost me, old and dirty as it is, four pounds’ (J.G. Millais I, p.162).

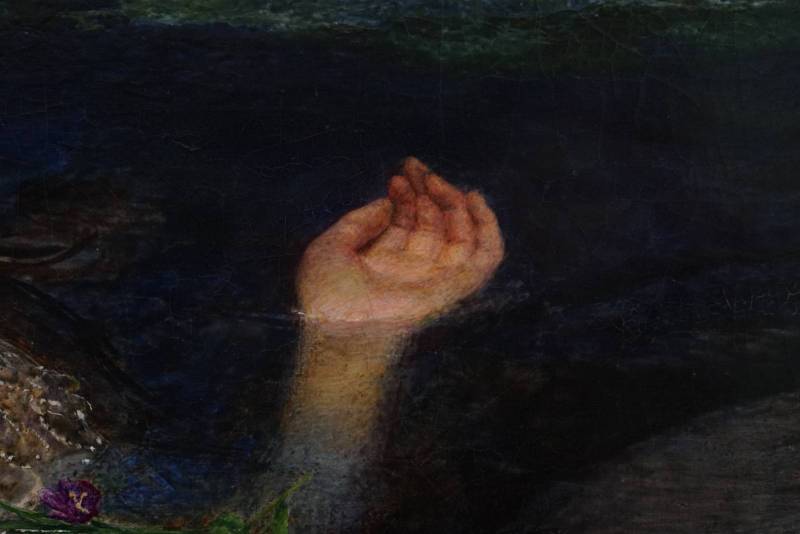

The Tate is fortunately, a museum that allows photography. So I had to try and get some good detail captures while there! These images, like the one at the first of the post, are large. Download them to get the full view and zoom in.

I think it is very interesting how Millais handled the way the arm extends down into the water. There is very little blending of brushwork throughout the painting, but many small strokes laid down side by side.

You can see some fairly pronounced impasto in places

Thanks for taking a look! I hope you enjoyed the post today.

Howard

Your posts are always delicious treats, Howard. Thank you very much.

Thank you Valerii, you are welcome! I appreciate your support, you are always good about commenting. 🙂

This is my favourite painting in the Tate, and I have the good fortune of being able to visit it frequently! Thank you for the wonderful photos, I never manage to get a good closeup!

You are welcome! I am jealous and I hope you take advantage of visiting often 🙂

I remember the first time I saw “Our English Coasts” by Holman Hunt. I was staggered to see pencil lines underneath in places! What a privilege to be able to stand and stare in such close proximity.

Yes! That painting has such wonderful refinement and detail. The craftsmanship is extraordinary. It is neat to see some lines coming through. It’s possible that they have become more visible over the last 100 years. Flake white, applied thinly, can become quite transparent over time.

Damn that painting is my second favourite after the famous Waterhouse. More interestingly I used to live two minutes away from the park where it was painted, and walked over a bridge over the very same stream that it was set in on my way to school. At some point in the 19th century the field and river housed a gunpowder factory too.

Yeah, that Waterhouse! Stay tuned for future post on that one. I have some pretty great closeups of it. 🙂

You wouldn’t happen to have some photos of that location would you? It would be cool to add them to the post. Let me know if you do. I am sure it is of course very different, but the comparison would be neat.

I went to Tate, but I did not see this piece (or any traditional pieces, really). Was I in the wrong section or something??? ?

Sounds like you were in Tate Modern. This Millais is in Tate Britain , which is further west along the river, past Westminster. You can take a river bus between them, which is a nice way to travel.

One of my very favorite paintings–a print hangs in my bedroom. Thanks so much for the high res pics. I’ll no doubt study them in detail!