A friend of mine passed along an essay written by Kathryn Shulz, “When Things Go Missing,” from The New Yorker. She writes about the concept of losing things; objects, experiences, memory, people, and uses the passing of her father as a way to describe “loss.” While I was reading it, it reminded me of a blog post that I wrote years ago about my grandmother who lived with us for years, and who eventually passed away. Here it is again for you to read…

~

Sometimes as I’m walking to the studio very early in the morning I shut my eyes when I reach a part of the neighbourhood that’s quiet and nobody’s around.

I just walk with my eyes closed.

When the sun is rising, and the air thick and hot, I close my eyes and walk for a few steps.

This morning I passed the old asian woman who collects bottles from the trashcans near my studio. I see her each day around the same time. She wheels a cart that’s filled with bags of empty bottles, and I wonder how early she wakes up to begin her day’s work. The past several times that I saw her I knew that she saw me too. Our eyes locked, and I could feel something pressing inside my throat; they were words that wanted to come out,

“Jo san.”

Which means, “good morning” in Cantonese.

The problem is that I don’t even know if she’s even Chinese… and if she is, then does she even speak it? Maybe she speaks Mandarin, or Toisan? But I guess the words “Jo san” is pretty universal within Chinese dialects.

The old woman reminds me of my grandmother who passed away when I was in high school. We were very close, and she helped raise me along with my aunt since I was about 3 or 4 years old. It’s not that my parents weren’t around, they were there – except that they had to work, both of them. My aunt came to live with us one day, and then my grandmother arrived soon after that. She was getting old and so my father being the eldest sibling, chose to take care of her. It’s typically what happens in Chinese households, the oldest son or daughter cares for their aging parents. But shortly after her arrival, it seemed like my grandmother was the one who took care of me.

~

I don’t recall the day, or month when she passed away, but I do remember the moment that it happened. She was already in the hospital having suffered a stroke before that. She couldn’t speak, and was partially paralyzed. I got a call from my father one afternoon telling me that she had died.

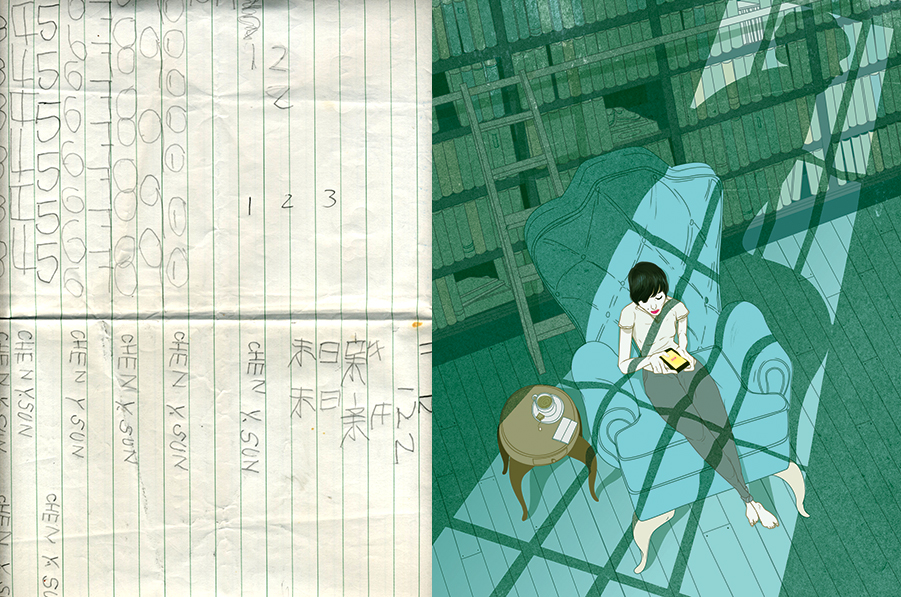

My grandmother and I spent a lot of time together, and at a very young age I had the privilege to witness at close range, the aging process. She arrived to Canada being able to stand and walk with a cane. But slowly, over the years her body began to break down because of arthritis, and so she needed the support of a wall, desk, or railing to help brace her while she moved. Eventually her body became so old that she spent most of her time in the bedroom, and because of her extreme immobility my father filled her room with everything she might need to keep her comfortable. A rice cooker, cookies and snacks, bread, hot water, tea, a television, papers and pencils, and magazines. To pass the time, my grandmother and I played boardgames, where she sat and rolled the dice and then watched me move both her and my figurine across the board. We played Bingo, where I was both the announcer and the players, filling my card and hers with plastic chips. Sometimes we watched exercise programs on television and my grandmother, seated, would raise and lower her arms over and over again, and then kick her feet in and out, the same way you might on the edge of a swimming pool. At lunch time, when I was in elementary school, I would go home to see her. I’d make lunch and then walk upstairs to her bedroom and sit on her bedside and eat. She usually sat in her armchair next to a broken Singer sewing machine that we used as a table. My family and I also taught her how to write her name and some numbers in English,

Chen Yut Sun

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

I combed my grandmother’s hair sometimes, and clipped her nails; each time tracing my fingers along the crooked bones of her hands and feet.

As her body began to break down even more in her old age, my father needed help caring for her, and so as a family, we all pitched in. She couldn’t go to the bathroom on her own anymore, and so my father taught us how to change her diaper. I understand how strange it would be for a boy who was barely a teenager to change his grandmother’s diaper, but for me and the rest of my family it felt very natural. At night, one of us would go into her room to tuck her in and give her a kiss. She would say in Toisan, lucky words and sentences.

“Grandmother loves you very much. Good luck. Good luck. Good luck. I wish you lots of good fortune. Good night.”

~

The old woman is hunched over slightly, her layers of clothing spotted with dirt from her morning ritual. She wears a small hat, I assume to protect her from the sun, but I wonder if it’s also to keep the wisps of stray hairs away from her face since the hat has barely a brim. I can see that the lines around her eyes and mouth are deep, and her nose is very slight. From a distance they read as two small dots near the center of her face.

She approaches the corner of the street at the same moment that I do.

We stare at each other for a few seconds, and then I feel shy and look away. I continue to walk about half a block down the street and then I turn back to see her from behind still lifting bottles out of the trash and placing them into her cart.

You are a good grandson. A good soul indeed.

<3

So powerful text, Marcos. You made me drop some tears because the memory of my own both grandmothers. Beautiful post.

Beautiful. I wish with all my heart that more of us could have such family. Whether we’re born into them or find them.

What a blessing to have had a grandmother like that, Marcos, and what a blessing to have had a grandson like you. <3 <3 It's a sign of deep love that you still see her in others and think of her so poignantly.

Nice Art….