We’re creating art history right now. You are a part of how future generations will look back to our times, our art, and how it will inform their own work. I believe our real contribution to its long history is about movement.

While so many struggle to find the next wave of evolution in Art, whether the paint is on the canvas, in the canvas, without the canvas, or hovering in cyberspace, narrative painting is still alive and depends greatly on movement within the frame.

Certainly, artists have been concerned about depicting motion for centuries, if not millennia. Sequentially drawn images can be traced back to Japan in the 1600’s that mimic comics of today. Farther back we find drawings on ancient Grecian urns showing figures moving in a story line. Even farther, the Assyrian Lion Hunt, in ancient Mesopotamia, showing specific points of the process of the hunt, similar to animation.

Animation can trace its roots all the way back to the cave painters showing animals in motion, even in primitive sequence.

The advent of photography changed a lot about painting moments. Before photography, people argued whether or not a horse’s legs were in contact with the ground when running. Once Eadward Muybridge solved the debate by snapping sequential shots of a horse galloping, proving that horses’ legs do indeed leave the ground, artists lost much interest in depicting staged images that were so important to depict reality before. Images started to show more impressions of the human condition. This broadened what could be shown in one picture.

Now the idea of time entered the canvas space. Viewers eventually connected with it because we humans already have an innate sense of time from thousands of years of pattern recognition.

Beyond learning to draw a model at rest, extra training is required to show the same figure in motion. While we can’t show an animation of an idea in a single painting (not yet anyway) we can capture a moment in time that lasts.

Learning over the centuries to depict reality on a two dimensional surface has taught us how to communicate with pictures. Describing space or telling time, our art is alive to the storytelling of a moment. It’s important to understand that whether we show someone at rest or in action, they are simply on pause, so the viewer can embrace the moment.

All imagery is in motion.

Here are some thoughts on how to think about and achieve good movement in your pieces. (there’s only three really needed here. Guess I’ll have to get back to you on the other seven!)

Actual motion

Showing good action depends greatly on not only proper anatomy of the subject in actual motion, but choosing the right moment. Action can be completely boring if always seen at the apex of the movement.

For instance, the wind-up to throw a punch. The arm pulls back and there are precious split seconds at the pause before the fist comes forward again. (I often wonder aloud at characters in a fight on TV: “you didn’t see that one coming?!” A ninja never winds up for a punch.)

You can find tons of paintings showing swordsmen at the top of the swing, where time slows before the sword heads down again, causing the figure to then ‘pose’ and that stalls the motion. Nothing wrong with that, but it does slow things down. The figure becomes frozen and doesn’t continue to move in our minds.

The moment to look for is either just before or just after the intended motion. As viewers, we’re familiar with this pattern. We have an innate sense of it and can feel what’s happening. The audience can feel when the hammer is about to drop.

About to stand, or just sat down? A painting of mine from To Capture The Wind

About to stand, or just sat down? A painting of mine from To Capture The Wind

Intentional motion

The moment one chooses to show can make all the difference between a pose and the movement that’s intended. When a figure walks or runs, the skeleton is catching itself as it moves, and the momentum carries it forward to the next step. A running figure can look silly if merely mimicking the action while fully balanced upright. The position of the spine will reveal if the figure is moving against gravity, thereby staying balanced, or moving with gravity, just barely keeping upright. Imbalance lends urgency to the moment and is more natural.

For example, if you show a figure falling in space and the movement is frozen, they instantly become stationary, in a posed position, as above. The impression becomes ‘floating,’ not falling. The position of the arms and legs can help impress which feeling you want, falling or floating, so anatomy becomes important again.

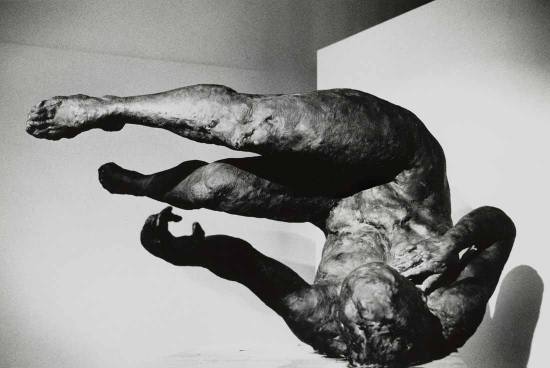

Eric Fischl’s sculpture of a Tumbling Woman captures a fabulous moment that doesn’t stop moving.

Eric Fischl’s sculpture of a Tumbling Woman captures a fabulous moment that doesn’t stop moving.

Sometimes, though, a pause in the action is necessary to show a heroic moment or to draw attention to something about the subject. It’s important to know the difference. When you understand that, it gives you a wider range of choices for the work.

Some of the best moments to my eye capture the subject in the moment after, when the figure is about to move into the next moment. The previous moments are implied—we imagine the previous action, and that’s inspiring to the brain.

Implied motion

So many artists create portraits that capture people sitting, at rest, glued to the spot. For hundreds of years, artists needed a subject to ‘hold still’ so their likeness could be captured.

Notice the movement across the canvas, even though she’s laying down. Amazing how it feels like she just flopped there! John White Alexander

Notice the movement across the canvas, even though she’s laying down. Amazing how it feels like she just flopped there! John White Alexander

I’ve been accused of painting portraits that appear to have motion in the subject, like they’re about to move. Some have claimed it’s the brushstrokes that give it motion. While this adds to it in my case, there are plenty of finely rendered images, and tons of photographs, out there that capture motion without blurred or painterly strokes.

This can be implied by the set of the shoulders, position of the spine and neck, twist and tilt of the head, shift of the pupils in the eye socket, position of the eyebrows, shape of the hair, and often the mouth, whether slightly or fully open. And most importantly, the position of the subject in the composition.

All of these aspects can be applied if you consider that the subject is living, breathing, and in the moment of life. We are always in motion, whether we just finished moving or are about to. Thinking of it this way can add great interest and curiosity to your images. It can also allow your anatomy skills to improve by thinking of the figure in motion instead of posing.

The impression of movement in a figure is held within the position of the limbs and the placement of the head over the spine. Like deciding the location of the horizon line in a composition, finding a figure’s center mass and it’s position on the canvas can determine how your image will be forever in motion.

Implied slow motion in my painting from 20,000 Leagues, Harvest

Implied slow motion in my painting from 20,000 Leagues, Harvest

I always strive to create brush strokes in my paintings that make it seem like the person/animal/monster/robot is alive. You definitely have the best brush strokes that continue to motivate me to keep pushing myself as an artist, thank you Greg! 🙂

The concept of “motion” being an integrated aspect of an image has just clicked a puzzle piece into place for me. Thank you!

I am also learning more and more that you actually have to enter the world you’re making a picture from. It’s not enough to just draw something as a symbol. You have to experience it first as a living thing in your mind and then do your best to take notes from your experience.

It’s like rediscovering all of the best parts of being a kid.

Howard Pyle called it the “supreme moment”. It is the part of the action in a scene that conveys the most suspense. He would often portray the characters in his scenes in the moment before or after the peak of action, saying that often that placing the subject in the midst of a violent action is less dramatic.A great example is of NC Wyeths image of Israel Hands climbing the ratline, knife ready to be thrown, and Jim Hawkins staring at him down the barrels of his muskets, just before he fires.

Thank you Greg for your incredibly instructive lesson on how to create drama in motion.